13. Internally Displaced People and Forced Relocation

"If villagers refuse to serve as porters, SPDC and DKBA troops will accuse them of supporting KNU guerrillas. Then, the soldiers would have the right to kill villagers who refuse to work. In order to save their own lives, five families left the village because they refused to work SPDC orders. Three of them lived in jungle as IDPs and two of them joined the KNU."

Village elder, Mae Tha Mu tract, Haling Bwe Township, Pa-an district, 2002. (Source: FTUB)

13.1 Background

The situation of internally displaced people (IDPs), in Burma remained critical throughout 2002. The U.S. State Department’s country report for 2002 on Burma estimated that forced relocations had produced hundreds of thousands of refugees, with as many as one million internally displaced persons.

"Throughout 2002 the military continued to forcibly relocate minority villages, especially in areas where ethnic activists and rebels were active, and in areas targeted for the development of international tourism." (Human Rights Watch World Report 2003)

In 2002, Human Rights Watch reported that tens of thousands of villagers in the ethnic insurgent areas remained in forced relocation sites or were internally displaced. It has been estimated that in 2002 around 170 villages have been burned down and 300 villages have been forced to relocate, in the Karen area alone. (Source: UN Wire) The most significant displacement has occurred in the border ethnic areas where the military regime has been at war with ethnic armed opposition groups for over 50 years. Ethnic minorities such as the Muslim Rohingyas of Arakan State, the Shan, Karen, Kachin and the Karenni, as well other smaller ethnic groups that live in the same areas have suffered disproportionately. Whatever their background, internally displaced persons in Burma live under conditions of severe deprivation and hardship. Almost all are without adequate access to food or basic health and education services. A large number of IDPs are women and children.

People in Burma become displaced as a result of SPDC policies that either directly or indirectly compel them to leave their homes. Villagers are subject to forced relocation by the SPDC as part of the military’s four-cuts program; for urban resettlement or "beautification" projects, which are often linked to the SPDC’s campaigns to promote tourism; and for rural resettlement programs. People are also frequently left with no choice but to flee their home villages when faced with resource scarcity, and the loss of their security and livelihoods that result from oppressive SPDC policies. Economic reasons for fleeing include: numerous demands for forced labor and portering; government crop quotas; ceaseless taxes and fees to support the army; army looting or destruction of property; and uncompensated loss of land or property due to SPDC development projects. Even more pressing are people’s fears of the torture, rape, arbitrary arrest and arbitrary killings perpetuated in border areas by the military. Finally, villagers also often flee in anticipation of forced relocation.

The majority of crossborder refugees report that before arriving in refugee camps they had spent some time living as IDPs. Currently however, those IDPs that would seek asylum in neighboring countries are finding it much more difficult to flee Burma, due to increasing SPDC control of the border, increased use of landmines in border areas, and the increasingly restrictive policies on refugees adopted by neighboring governments.

Thai Policy towards IDPs

As a non-signatory to the 1951 International Convention on Refugees and its’ 1967 protocol, Thailand argues that it is under no legal compulsion to provide asylum for any refugees. Thailand does not allow the establishment of any refugee camps for, and denies refugee status to, all people from Shan state despite very heavy fighting there throughout 2002-03. The Shan Human Rights Foundation estimates that since 1997 over 300,000 people in Shan state have been forcibly relocated, and some 150,000 have sought refuge in Thailand. The Thai government estimates that there are an estimated 110,000 refugees in Thailand, which represents only part of the Burmese IDP population. (Source: Refugees International 2003) Only those refugees from recognized zones of conflict, fleeing directly from fighting officially qualify as refugees in Thailand. Refugees International reports that: "This confusion about who actually qualifies to be called a refugee is compounded by the refuge-seekers themselves. Rather than describe themselves by their starting point — i.e. the reason they fled Burma — many people look to their present situation, i.e. their status as illegal workers…Forced labor and forced relocation are human rights abuses, they are not "economic reasons," and those people fleeing such violations are escaping first and foremost from persecution." (Source: Development of Democracy in Burma, Testimony to US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Subcommittee on East Asian and Pacific Affairs by Refugees International,18, June, 2003) In addition, RI notes that the Thai army and border police have effectively sealed off the border from IDPs seeking refuge.

"The displaced endure abuses rather than seeking asylum because they know that coming to Thailand can be dangerous and that denial of entry at the border happens routinely. News has trickled back inside Burma that even if IDPs can find a secret route into Thailand, they may not be allowed into refugee camps. There are no guarantees that they will be protected from abuse by Thai authorities or receive humanitarian assistance. Thailand’s strict policy towards refugees is achieving its goal of deterrence, causing IDPs to stay in Burma at great risk to their security and well-being.

To qualify for refugee status in Thailand, Burmese must be able to prove that they are "fleeing fighting," which is defined as literally being shot at within hours or, at most, a few days of reaching the border. Only a fraction of the three to four thousand people seeking asylum in Thailand each month qualify as refugees under this narrow definition. As a result, many refugees fleeing human rights abuses are rejected and left with few options for protection and assistance. To make matters worse, in a further effort to deter refugees from entering Thailand, the Thai authorities halted the entire refugee screening process for the past year, leaving no mechanism available for refugees to enter camps. The Royal Thai Government has so tightly circumscribed UNHCR’s role in protecting refugees that, in effect, the UN refugee agency is unable to carry out its core protection mandate along the border with Burma.

In summary, there are few options available for IDPs to find a safe haven. Knowing of the threats they could encounter on their journey to Thailand, the uncertainty of being allowed to cross the border, and the likelihood that they will be denied access to refugee camps, many prefer to live in hiding in the jungles or in government relocation sites, where on-going human rights abuses and threats to their survival are a day to day reality." (Source: Refugee International 2002)

Land Confiscation

The SPDC has subjected people to displacement for both economic and security reasons. Government displacement programs have been in place since the late 1960s, and possibly before. Since that time, under the guise of regional or area development, private land and plantations from civilians have been confiscated by the military - without any compensation - for military plantations, farms or animal breeding ranches, or for the construction of roads, railways, hydroelectric power plants, large dams and small scale infrastructure projects. In addition, the regime has forced numerous urban populations to move into areas away from city centres. In the 1990s the trend has been for the military to displace civilians from cultivable land which is then used for the construction of military bases or for income-generating projects.

The "Four Cuts" Campaign

In the volatile border regions, displacement campaigns have been aimed at securing combat zones, cutting off civilians support for insurgents, and curtailing the activities of ethnic armed groups. These activities fall under what the SPDC refers to as the ‘four-cuts’ policy. This program was introduced in 1974 with the aim of cutting the supplies of 1), food, 2) funds, 3) recruits, and 4) information to the resistance groups. In some border areas which the regime had labeled brown areas, forced relocation programs were carried out systematically. In other areas, which were classified as black areas, all villages were destroyed, fields and paddy barns were burnt, and anyone found in the area was shot. These campaigns against civilians were intensified after the 1988 pro-democracy uprising. Currently under the four-cuts campaign, villagers suspected of having contact with the resistance are detained, tortured, and executed; regime troops systematically extort and pillage villagers’ crops, food supplies, livestock, cash and valuables; and villagers are forced to labor for army projects. Any village that is suspected to be supporting the opposition is forced to relocate. In 1996-1997, the military regime launched programs to forcibly move or wipe out all rural villages in areas not directly under the their control. As a result of these intensified programs to destroy the populations in the ethnic areas, the number of people displaced has continued to increase dramatically.

When a village is forced to relocate, the villagers are usually told that they will not be permitted to go home until the opposition groups have capitulated. The SPDC issues written orders addressed to village headmen, which specifies the date by which the entire village must be relocated to a designated site. Relocated persons are not compensated for their homes nor are they given enough time to collect all of their belonging. Villagers must leave behind the majority of their belongings, including their livestock. Often people must also leave behind elderly and sick relatives. The areas cleared of villagers are then designated as "free-fire" or black areas. Houses, villages, and crops left behind are often pillaged and then dismantled and/or scorched to prevent the return of villages. Villagers seen in the areas of their former homes are considered to be rebel soldiers and shot on site. In some cases landmines are laid on the roads leading into villages, or in abandoned fields and homes.

13.2 IDPs in Burma

There are four types of displacement in Burma:

1) Displacement into state-controlled relocation sites and satellite towns

Villagers forcibly relocated generally are required to move to one of the areas designated as "relocation sites" by the SPDC. These sites are most often located in other villages or towns near army bases, car-road sites where there are no villages, and barren areas where there are no resources or transportation. In the cases of urban resettlement or "beautification" projects, the townspeople are moved to outlying areas of the city called "satellite towns."

Satellite Towns

These new towns are made of populations forced to relocate by the military government, and are located in the outskirts of cities, usually a few miles out where there are very few facilities. In the last five years, the junta has forcibly resettled tens of thousands of potentially restive poor people from city centers into these distant slums. Clean water is scarce and sanitation is poor in these slum areas. In addition, the people who are relocated face great difficulty as public transportation into the cities is either nonexistant, or else extremely poor and unreliable. Employment in the new satellite towns is scarce. There are inadequately equipped schools in these towns, but health care is a problem as the few clinics that exist are understaffed and under supplied and the city hospitals (also understaffed and under supplied) are difficult to get to.

The Relocation Sites

In most of the places that have been chosen as "relocation sites" by the SPDC, little preparation or organization is done in order to receive the displaced people. The SPDC is unconcerned whether or not water, food, cultivatable land, employment and services are available in the new areas. The burden for sheltering and caring for the displaced at relocation sites generally falls on the local community. If the relocation site is part of, or near another village or town, this extra burden results in increased depletion of the resources of the original population. No humanitarian assistance comes from the government, although at some sites there is very limited assistance from church organizations. In some cases, rice has been distributed to the IDPs during the initial relocation period, yet these rations are insufficient and the distribution period is short. One refugee who came from the relocation site at Mawchi in Karenni State stated that rice intended for the relocated people was diverted and sold by local township authorities.

The SPDC troops force the villagers in the relocation sites to work on a daily or weekly basis; generally one person from each family must go. This forced labor includes clearing bushes and trees from the roadsides both inside and outside the relocation sites, cleaning military buildings, cultivating land for the military bases, hauling water for the troops, building fences around the military camps, digging bunkers, road construction, portering for the military and other general servant work. The villagers are also forced to work in the infrastructure projects in the area. Moreover, they are made to pay various fees for development projects, military funds, food for visiting troops, and so on.

Services at the relocation villages vary from site to site, as each site is under the responsibility of relevant state or township committees. However, in general there are no arrangements made to provide services for the relocated people.

Access to water varies – in some sites wells have been dug in addition to streams and lakes. Yet in some sites, such as the Shadaw relocation site in Karenni State, the lack of drinkable water has resulted in several problems, including sickness and deaths caused by chemicals that were added to the water in an attempt to clean it.

Sanitary facilities are usually nonexistent for the IDPs and they either are required to build their own, or use outer areas of the sites for latrine purposes.

The poor water and sanitation at the sites, among other things, has resulted in higher levels of sickness and mortality, yet health care facilities are either missing altogether, or else seriously under-equipped and under-supplied.

There is no access to electricity in most sites, and in some sites, such as Shadaw relocation site in Karenni State, torches (flashlights) are banned and dry cell batteries are not permitted to be sold in the site. This lack of provisions for night lighting increases the vulnerability of women, among other things.

Education facilities are also insufficient or nonexistent. In most cases, the relocated people establish makeshift schools themselves. If there are pre-existing schools, school buildings, teaching materials and teachers are never sufficient, and families often do not send their children to school as they cannot afford the school costs, or they require their children to help in the family’s attempts for survival. (See chapter on health and education for more information)

At all relocation sites in Burma, access to farmland and employment is a serious problem for the relocated villagers. In some sites, IDPs are able to access farmland around the relocation site, yet this allocated land is usually insufficient for basic survival or unsuitable for farming. In other sites, access to surrounding land is denied, especially when villagers are relocated to sites where local residents are already farming the land, either for themselves or for the military. New refugee arrivals at the Thai border in 1999 reported that they had been able to find daily labor at local farms near the relocation sites, earning between 40 and 120 kyats per day. In some cases, villagers are permitted to return to their former farms and plantations, yet due to the restrictions imposed on their trips out of the sites and the dangers these villagers face outside of the sites, most are unable to make a living in this way.

Villagers in relocation sites live in constant fear of the violence and demands of the state forces, both inside and outside the relocation sites. Villagers are not permitted to leave the sites without passes, which they must purchase from either SPDC soldiers or local authorities. The passes are usually only valid for 1 day, from dawn to dusk, although in rare cases week passes have been granted. (see chapter on the freedom of movement) This leaves the villagers little time to travel to their places of work, complete their work, and then return. In addition, security for the villagers outside of the relocation sites is notoriously bad. Villagers seen outside the camps are vulnerable to capture, arrest, torture, and killing, even if they hold valid passes, as they are accused by SPDC troops of leaving the camps to support rebel forces. Women are especially vulnerable, and many cases of rape have been reported by women who have gone outside the camp to forage for vegetables or get water. (see chapter on women) The local authorities do nothing when cases of abuse are reported to them by the villagers.

2) Displacement into areas under full SPDC control;

Many villagers suffering from abuse under the SPDC four-cuts program, or who have been told to relocate without a specified site have chosen to resettle in areas under full SPDC control, which they feel are safer and more stable than the conflcit areas, or where they have friends or relatives. Yet as most of the displaced villagers are farmers, they face many difficulties when they are forced to move into new villages or towns. Available land in these areas is often scarce and the search for other employment in new areas is difficult. In larger towns or cities farmers are often forced to seek work as day laborers in low paying jobs. The families who have been forcibly relocated also usually move without being able to bring all their belongings, adding to their problems of resettlement. Villagers sometimes move to villages and towns where they have relatives, but their relatives are often not able to provide the extra support needed, as they themselves are suffering. In addition, these IDPs living in areas under SPDC control are subject to the same abuses as the other villagers around them. These include the demands for forced labor, fees, and restrictions that are commonplace across Burma. Yet because the abuses committed are sometimes less then in areas under the four-cuts program, many villagers choose to face the risk of moving to areas under full SPDC control.

3) Displacement into areas and camps controlled by armed opposition groups

Villagers who have been forced to flee their homes and villages for any of the above mentioned reasons, are sometimes able to seek shelter in areas controlled by armed opposition groups, where they feel they have some protection from SPDC abuses. Several of the armed opposition groups operate camps and resettlement sites in their areas of activity. However, in these camps and sites, supplies and services are very limited, and often the shelter and supplies offered are only temporary. Access to food, education and health varies from site to site, as does the level of security. In some camps and sites schools, health care and other services are provided for a limited number of IDPs, and the area is safe from SPDC attack, yet in almost all such places, there are no employment opportunities. Therefore, the IDPs have to live off of whatever the opposition groups can provide for them.

4) Displacement into jungles, fields, and other remote, usually "free fire" or black areas of Burma

There are nearly 1 million people estimated to be hiding in the border conflict areas of Burma, and this is the IDP group with the least access to basic survival needs. These villagers have fled into hiding, despite the risks, because of various factors. These IDPs include:

- Those who flee SPDC troops in advance of their arrival;

- Those who can no longer stand the abuses they suffer in their villages;

- Those who were ordered to move from their village to a relocation site or other place, and who chose not to do so; and

- Those who have fled from relocation sites due to unlivable conditions.

These IDPs are regarded as enemies by the SPDC troops, as the areas where most villagers hide are located in black or "free-fire" zones. They are shot on sight, or else captured, tortured and then sometimes killed whenever they are found. Their shelters, rice plantations and belongings are looted or destroyed when discovered. Under the guise of ridding areas of opposition forces, the SPDC has launched several "search and destroy" operations, in which soldiers root out and destroy everything they see in the area including people. The troops often plant landmines on paths that they suspect the IDP villagers use, and they practice a "scorched earth" policy of looting, destroying and burning any signs of habitation or food supply. Troops have even been known to cut down fruit trees growing naturally in the forest in these operations in an attempt to make it impossible for anyone to survive in the forests or jungles.

Villagers often hide in areas near their old villages and risk attempting to work and harvest their crops in secret. This work is extremely dangerous, and if crops are discovered by soldiers, they are burned or destroyed. If the villagers are unsuccessful in harvesting rice, they forage for other sources of food in the forests. Villagers in hiding, for the most part, are unable to travel outside of their area of hiding to purchase other necessities, and must make do with what they can find around them.

Health is a major concern for people in hiding. Life in the tropics without shelter or adequate food leads to high sickness and mortality rates from malnutrition, diarrhea, malaria, minor injuries and other easily preventable illnesses. With a complete absence of health care facilities, people mainly rely on herbs and traditional medicine. Although there are some healthcare teams which seek to reach IDPs, the medicine and care they are able to provide is insufficient for the numbers of IDPs in hiding across many border areas.

IDPs hiding in the jungle are sometimes able to operate temporary makeshift schools with volunteer teachers. These schools lack any supplies, and are forced to shift from place to place depending on SPDC activity. With the increase in SPDC activity, in recent years, and the common occurrence of "search and destroy" operations, the number of these schools has been greatly reduced.

13.3 Situation in Arakan State

Throughout 2002 the Muslim Rohingya population continued to be subject to large scale internal displacement as they have been over the last decade. Forced relocation has not been uncommon. Most relocation is connected to military efforts to install military camps, to build administrative or religious infrastructure, to move the Muslim Rohingya population to the north of the state and to settle Buddhist people throughout the state in "model villages." Small minorities of Arakan (notably the Mro) have also been relocated from their mountainous and remote homelands to the plains.

Within Arakan State there is significant displacement due to the government’s continuing discrimination and repression of the Rohingya Muslim minority. The SPDC’s abuses against Rohingya Muslims, including denial of citizenship, forced labour, and arbitrary confiscation of property, continue to prompt new refugee flows and limit the reintegration of those who have returned from refugee camps in Bangladesh. (For more information about discrimination and displacement of Rohingya Muslims see chapters on Freedom of Belief and Religion, and Situation of Refugees).

Muslim villages outside the far north are becoming rare. Most of the Rohingyas who lived in the Kyauktaw, Mrauk-U or Minbya districts have been forcibly displaced to the north over the past few years. These forced relocations, which go hand in hand with serious human rights violations, have been denounced by the UN Special Rapporteur on Burma, notably in February 1993 and January 1995. According to villagers still living in Rathidaung, out of the 53 Muslim villages existing in the district before 1995, only two remained in 1999. The construction of model villages for Buddhist settlers in the north of the state also entails the forced relocations of Muslims who are moved to less fertile lands, usually without adequate time to prepare or any compensation.

SPDC Plans to Establish More Settlers’ Villages in North Arakan

On 16 November 2001 it was reported that the SPDC is preparing to establish more settlers’ villages in the Muslim majority border areas of north Arakan during the 2001-02 dry season. Instructions have already been sent to local authorities to make the necessary arrangements for this. So far, 33 settlers’ colonies, dubbed ‘model villages,’ have been established in Maungdaw and Buthidaung townships on lands confiscated from Muslims. The new settlers are ethnic Burmans, Rakhines and some members of hill tribes from Arakan Hill Tracts in eastern Burma. They have all been provided with readymade houses, farmlands, bullocks and carts, free rations for more than one year and free labour from Muslim forced labourers.

Although the above settlements are established in the border areas they are not under the control of the Na Sa Ka (border security force) like Muslim villages. Instead they are controlled by the Headquarters of Military Intelligence under the Western military command and Township Peace and Development Council in Buthidaung. These new settlers have been responsible for various crimes against Muslim villagers including picking fights and stealing livestock. (Source: Arakan News Agency)

Forced Relocation in Arakan State - partial list of incidents 2002

SPDC Army Forces Carpenters to Build Houses for Burman Settlers

On 7 March 2002, a large number of carpenters from Maungdaw and Buthidaung Township areas have been forced by the SPDC Army to construct houses for Burman Settlers. According to a Construction Department engineer, the SPDC is constructing houses in about one dozen "Model (Sanpya) Villages" in Buthidaung and Maungdaw townships. Seventy Burmese families consisting of 296 people total, from central Burma will be relocated in the new houses built in the "Model Villages" of Pe-yung, Tharay-kung-baung, Mora-waddy, Udaung-kye-rwa, Aung-tha-bray and Naing-ra-gaing, in Maungdaw township. The SPDC has ordered the local carpenters to complete the houses before 27 March, the Burmese Army (Tatmadaw) Day.

It was learnt from some of the residents of the ‘model’ (otherwise known as SPDC) villages, that since February 3 2002 two families who had been forcibly relocated from Rangoon to Aungthabray ‘SPDC’ village, fled to unknown destinations. These relocated villagers took their belongings with them and left behind a bullock-cart and two acres of paddy land.

According to the Contruction department engineer and sources in the Maungdaw township administration (Mawata) the new houses being built in the dozen model "SPDC" villages will house people relocated from central Burma. People being relocated to Maungdaw include the homeless, lepers and people with HIV/AIDS. The carpenters building these houses are paid below market wages by the SPDC. (Source: Narinjara)

Land Confiscated for Model Villages

Throughout April 2002 the SPDC have been confiscating privately owned land in the border townships of Maungdaw, Rathedaung and Buthidaung . On 1 April, Mayaka Township Peace and Development Council Chairman of Maungdaw, Captain Hla Paw and his group met with U Thein Tun, the leader of Payrung model village and took him to the east of the village. There they surveyed 135 acres of hilly area owned by neighbouring villagers. Afterwards the authorities confiscated the land with plans to distribute it among the residents of Payrung model village.

The confiscated land will be distributed after the traditional Thaung-gran New Year festival that ends on 17th April by casting lots among the mostly Burman residents of the model village. There are now more than thirty such model villages in three townships which are occupied mostly by settlers brought in from central Burma. The residents of these villages are reportedly former hardcore criminals, HIV patients, drug addicts, and retired military personnel. Residents are concerned that the establishment of Na-a-fa model villages in the area will increase crime rates and the spread of HIV to the local population. (Source: Narinjara)

NaSaKa Forcibly Relocates Villagers

Between 7-16 June, the NaSaKa troops forced 39 families from Zedibraung village, Laungdung village tract, Maungdaw Township to relocate to Chaung-they-braung (Sin-the-byin) village, in the northern part of Maungdaw. This forced relocation left the villagers landless and homeless. Though the monsoons were in full swing they were left with no land to cultivate. Due to the torrential rains, the villagers faced difficulty in building houses in the area where they were forced to resettle. This area is located in an inaccessible part of the township where there are practically no road links, and materials like bamboo, timber and thatch for building houses are not available in the nearby hills.

The Nasaka border security forces evacuated the villagers following the November murder of a prostitute by four Nasaka members in a camp close to the village. The murderers decamped with the arms and ammunition. The NaSaKa have alleged that the murderers came from the village, and carried out an ‘investigation’ into the incident which involved the detention and torture of many villagers including women and teenagers. The NaSaKa have accused the villagers of being accomplices to the murder, and the villagers believe that they were relocated as punishment for this. (Source: Irrawaddy)

Rohingyas Continue to Flee to Bangladesh to Escape Forced Labor and Starvation

On 7 October 2002 Narinjara reported that increasing numbers of Rohingyas had entered Bangladesh after fleeing starvation and forced labor in Burma. In Area # 8, Maungdaw Township, controlled by Myin Hlwett Nasaka (Border Security Force) alone, at least 16 Muslim Rohingyas have left for Bangladesh in recent weeks to escape conscription for forced labour and widespread starvation caused by rising rice prices.

In Bangladesh, the new arrivals are not recognized as refugees, and are usually unwelcome by locals as they are viewed as a ‘menace.’ While it is difficult to estimate the total number of Rohingyas who have crossed into Bangladesh in recent months, many journalists in Cox’s Bazaar estimate the number to be between 4 and 5 thousand.

On 5 November 2002 a fresh wave of Muslims from Burma including Rohingya Muslims, reportedly crossed into south-eastern districts of Bangladesh through Burma’s western border.The influx has caused wide concern among the local administration. At the end of November an estimated five thousand illegal Rohingyas had crossed the Naaf River and taken shelter in Cox’s Bazaar, according to a news item in the Independent ( 26 Nov) from Dhaka. The Rohingyas arrived fleeing increasing demands for forced labour by the Burmese junta officials. Sabib Ali (not real name) a resident of Maungdaw Township who is now living in Cox’s Bazaar, reported that there is an undisclosed famine-like situation prevailing in the area where the majority of Rohingya Muslims live. These harships are a result of wide-spread conscription for forced labour, rising costs of basic commodities, and high levels of unemployment. This man estimated that there were approximately 9,000 to 10,000 illegal Rohingyas currently lving in Cox’s Bazaar.

Sabib Ali also reported on further persecution that drives Rohingyas out of Burma: "The Burmese junta imposed travel restrictions on the movements of the Muslim Rohingyas also make our life miserable as we cannot even move from one village to another without the permission of the local junta officials. That does not come without a large bribe. Our wedding also needs permission from the junta to take place. In the coming Eid-ul-fitr, the greatest of Muslim festivals, we will have difficult times observing it as most of the Muslim population is hard-up due to all the restrictions." (Source: Narinjara)

Muslims Forced to Give Rice for Burmese Settlers.

On 18 November 2002 Muslim villagers living in Maungdaw Township near the border with Bangladesh have been forced to give rice to Burmese settlers who have been relocated in the area by the SPDC. Each of the Muslim families in the villages around Padummala village, situated 10 miles south of Maungdaw Town, have been ordered by the SPDC officials to give fifteen baskets (about 180 kilo) of rice during the current harvest.

Reportedly, many of the Burman settlers who were brought to the area in 1995-96 were previously homeless. One local village elder reports: "Many of them are single persons either jobless or of doubtful livelihood…many are believed to have had connections with crime in Burma proper."

After being brought to the Maugdaw by the SPDC, each of the settlers was given three acres of paddy land, a buffalo cart, a pair of bullocks, and a house with a corrugated iron sheet roof. As most of the settlers were unable to earn a livelihood, many were soon forced to sell the corrugated iron sheets to buy food. To date many of those resettled have surreptitiously left for their previous homes in central Burma. The remaining settlers continue to be a heavy burden for the native Muslim and Buddhist villagers living nearby, since these villagers have to do all the agricultural work for them in addition to giving them rice demanded by SPDC officials. (Source: Narinjara)

13.4 Situation in Karenni State

Brief Summery of the Situation of Internally Displaced Persons in Karenni State

Currently in Karenni State there are three types of displacement: conflict-induced; development-induced; and displacement arising as a result of resource scarcity. Conflict exists in these areas as a result of the Karenni National Progressive Party’s (KNPP) efforts to cecede from Burma. These efforts have been strongly resisted by the military government, with displacement used as a tool since the 1960s to secure areas from rebel forces. This displacement has included the confiscation of land and natural resources by the military, greatly impoverishing local communities.

The successive military regimes of Burma have three times carried out forced relocation programs in Karenni State. First under the BSPP, particularly in No. (2) District of Karenni State, when an estimated 50 villages were destroyed and burnt down and tens of thousands of villagers in the area became homeless. Second, under the SLORC, who forcibly relocated many villages in No. (3) District of Karenni State, and about 500 of the villagers in the area died from diseases such as malaria and diarrhea. Then in 1996, the military government again carried out its forced relocation program across the Karenni area. A forced relocation order with the deadline of July 7, was first given to villagers living between the Salween and Pon rivers, the two major rivers in Karenni State. According to the order, the villagers had to leave their villages in seven days and go to forced relocation sites designated by SPDC. The villagers were warned that seven days after the order, the area would be declared a free-fire zone, and anyone found in the villages or in the free-fire zone would be considered a rebel and shot dead on sight. In the year 2000, the SPDC allowed many Karenni people who had been living in forced relocation sites since 1996 to go back to their own villages. The villagers however, were ordered to report to the nearest SPDC outposts at least once a week. Currently, they are not allowed to stay over night at their farms, and are required to possess passes, which cost 20 kyat in order to travel to their farms during the day. Villagers are prohibited from carrying military uniforms or traditional guns used for hunting, and from trading in medicine or batteries, and the purchasing and selling of rice is restricted. Villagers are allowed to travel from village to village only twice a week- on Tuesday and Thursday. When they travel they are checked for their National ID cards, and are required to pay 20 kyat at every checkpoint.

Partial Return of IDPs from Southern Shan State

In 1996 people from Karenni State fled into Southern Shan State’s SNPLO area and joined a population of Karenni that had moved there as IDPs twenty years ago. When they arrived in Shan State, they started wearing Pa-O clothing rather than their own. They did this because they worried that if the SPDC troops saw them wearing Karenni clothes, they would be victimized. The people there farm rice and opium. Those who arrived after 1996 are waiting for the political situation to improve before returning. In the summer of 2002, several villages returned to Karenni State although there is still no security, health care or education. Before returning, they informed the SPDC authorities based in their old township. The SPDC authorities replied that they could return as long as there is no fighting around their village and they are not allowed to contact the KNPP. They threatened that if any fighting took place, they would come back and burn down the village. (Source: Burma Issues)

Villagers Displaced by Government Infrastructure Projects

"Recent data indicate that while villagers have been displaced by fighting, it is also government-initiated development schemes, aimed at separating people from non-state groups by forcing them into relocation sites, that has resulted in most displacements since 1960s. These schemes were responsible for the wide-scale displacement of about 25,206 people in 1996 alone. Of these, 11,669 are known to have moved to relocation sites, 4,400 were registered in refugee camps and a further 9,137 unaccounted for. Since 1998, many IDPs have moved out of relocation sites back to their villages (some voluntarily, while others have been ordered back) or to refugee camps in Thailand. (BERG September 2000)

"Another project that caused an unknown number of displacements was the rail link between Loikaw and Aung Ban on the border with Shan state. Work on the railway, which is 40 kilometres long, started in 1991 and was completed in 1994. During this time, 31 acres of farmland plus 9 acres of land in Loikaw city were requisitioned to make way for the line [...] A further 24 households were displaced in Loikaw to make way for additional but unspecified transport infrastructure projects. In each case no compensation was made. In addition to the displacements which came about directly as a result of the railway, the building of the embankments disrupted (in some cases blocked) irrigation systems and supplies of water to local farms. This then resulted in a further voluntary displacement, the extent of which is not known." (BERG May 2000)

"Land ownership is extremely fragmented and a significant proportion of the population is landless in Karenni State. There are large numbers of displaced connected to economic interests in the area. With an economy based on access to teak resources - and of equal importance, hydro-electric power and mining concessions - the government has in some cases taken steps to pacify areas, quelling so-called ‘insurgency’ problems before undertaking investment in the areas. Much of this displacement is carried out in military style outside any civil or legal framework. Moreover, the deterioration of the formal economy has fostered the growth of an extra-legal state economy, focused on the extraction of natural resources that all groups, including the state, rely on. In the absence of lasting and substantive peace, the displacement of civilians is likely to continue. The current cease-fire agreements in the state appear to be ad hoc economic deals rather than a process aimed at political resolution and peaceful reintegration. The cease-fires in fact have allowed armed groups to legitimise their the extra-legal state economy and added to further factionalism in the competition for increasingly scarce resources." (BERG September 2000)

Situation in Relocation Sites

Relocation sites have been scattered throughout the state at Shadaw, Ywathit, Mawchi, Pah Saung, Baw La Keh, Kay Lia, Mar Kraw She, Tee Po Kloh and Nwa La Bo. As more villages were relocated, more sites such as Daw Dta Hay were created. All were under complete control of the Army, usually located adjacent to new or existing Army bases. Although living in the jungle was fraught with problems associated with the danger of the patrols and finding food to eat, some people still tried to remain there, but many gave in to the order and moved to the relocation sites. Conditions at the relocation sites were extremely basic, with the lack of proper shelters, pure drinking water, and little food or medicine contributing to many deaths from starvation and illness. At each of the large sites, there is evidence of an intention to provide health care to IDPs, either at a health facility inside the site or at a nearby health centre. In practice, however, given the general constraints to the public health system, services were not utilised well. With facilities both under-equipped and under-supplied, health care providers were often left to do the best they could. In some of the other sites, such as Htee Poh Kloh and Mar Kraw Shay, refugees said there were no health facilities at all.

Approximately, 1000 villagers in No. (1) District alone died in both forced relocation sites and hideouts. International relief organizations have no access to the sites. Leaders from a couple of local churches tried to provide food and other needed materials for the villagers in the hideouts but they were not allowed to do so. The villagers were not allowed to go out of the sites to farm. Recently, villagers from some sites have been allowed to farm outside the sites, but they must return at the end of the day. The villagers also face forced labor and portering. A certain number of villagers have to go to the nearest strongholds of the SPDC everyday where they are forced to offer free labor such as digging trenches, making fences, fetching water and collecting firewood. Women and children are also made to do forced labor.

Perimeters of the relocation sites are reportedly largely left unguarded and the fences that the villagers are often forced to build are primarily around the army camps and not the actual relocation sites. Troops are lax in securing the camp perimeters realizing that villagers have no choice but to forage for food outside the camps. This is often used by the villagers as a chance to flee the relocation site and go into hiding in the jungle, usually near their old villages. The continual flight of residents has been ongoing since the relocation sites were first established, and many villagers report that a large number of people have already left the relocation sites in search of food and that the current populations of the relocation sites are much less than what they were initially. (NCGUB, KNAHR)

Situation of IDPs in Hiding

A large number of villagers who were ordered to leave their villages in 1996 remain displaced outside relocation sites. In the first few months following the order to relocate, there were at least 13,537 IDPs living in hiding. These villagers find their lives are in great danger as they are constantly being hunted by SPDC troops. While on the run and in hiding the villagers suffer from many kinds of diseases such as malaria, diarrhea and skin infections. Many villagers have died from treatable diseases. Villagers fall ill frequently due to lack of proper shelter. They are all the time on the move, especially when SPDC troops approach their hideouts. While on the move, villagers have to travel in all kinds of weather, sleep on the ground, eat what they find in the jungle and drink impure water. Many IDPs in hiding have also died from starvation, as most are not able to farm. These IDPs also have no access to education. (CSW November 2000)

Forced Relocation in Karenni State - partial list of incidents 2002

On 4 and 5 May, 2002, Burmese Township authorities from Mawchi and Pasaung gave a verbal order to the villages in Lopwakho District, to move the Mawchi and Pasaung relocation sites. This was the second time they had been ordered to relocate by May 27. People living in these villages had been moved to the relocation sites in 1996 and returned to their native villages at the beginning of 2000. After having re-settled in their native villages, they were forced to work on the old Mawchi-Taungoo road repair project by the Mawchi military commander in 2001 and were told to complete it at the end of the year. However, the road repair project could not be finished according to schedule, due to lack of manpower.

Because of their previous painful experiences in relocation sites, the people decided not to move to the sites, which are also known as concentration camps. Instead, some traveled to Thailand and some people traveled to the Karen area bordering Thailand. Local Thai authorities denied shelter to those people who crossed into Thailand and tried to push them back across the border into Burma. Currently these people are living a precarious existence without safety or adequate provisions. (Source: KNAHR)

On 15 June 2002, the Burmese commander from LIB No. 302 at Shadaw base ordered villagers from Tin Loi, Shadaw Township, who had just recently re-settled there to move their village once again. The Burmese commander did not say where the villagers were to go. The village chiefs approached the Shadaw military commander the next day requesting that he re-considered his order and also explained their situation. However, their appeal was rejected and they were told that if they failed to move within 3 days, the troops would raid and burn the village down. (Source: KNAHR)

13.5 Situation in Mon State

While not on the same scale as in neighbouring Karen State, forced reloctions continued to occur in Mon State throughout 2002. The incidence of forced relocation decreased after 1995 when the New Mon State Party ( NMSP) made a cease-fire agreement with the SLORC. However, the continuation of Mon resistance under the MRA (Mon Revolutionary Army) alongside continuing operations in the area by the (Karen National Liberation Army) KNLA has ensured that much of Mon state remained a war zone throughout 2002.

In October of that year in Bangkok the umbrella organization of the Mon asked the UN human rights envoy to allow the International Committee of Red Cross access into the areas of displaced persons. Sunthorn Sripanngern, General Secretary of the Mon Unity League (MUL), asked for ICRC access into the Mon area of internally displaced people at a meeting with the UN human rights special envoy, Mr. Paulo Sergio Pinheiro. According to an MUL spokesperson, the meeting was organized by Mr Nicholas Howen, UNHCR Regional Representative for Asia-Pacific, and attended by NGOs working on Burma and the Head of the ICRC Regional Delegation for East Asia, Mr Jean-Marc Bornet. Several armed groups including SPDC troops are active in the so-called cease-fire zone of the Mon making the situation there arguably worse than before the cease-fire deal with the SPDC in 1995. (Source: Kao Wao, November, 1, 2002)

In early 1990s "…when the NMSP had already lost much of its former territory - forced labor, forced relocations, arbitrary taxation, and the extrajudicial execution of villagers suspected of assisting Mon soldiers were the main causes of flight. The SLORC set about developing the Mon state and Tenasserim division peninsular, embarking on a massive program of road and railroad construction and clearing economically important areas of people who might support the Mon and Karen ethnic armies. The single most common reason for flight over the next five years was the construction of the railroad between Ye and Tavoy (a distance of 160 kilometers). In late 1993 the SLORC started rounding up villagers in Mon state to provide labor to build the railroad, and as of May 1998 the use of forced labor on this project was continuing. Over this period of time, thousands of Mon, Karen, and Tavoyan villagers were forced to work at the site for up to two weeks per month, sometimes more. As in other forced labor projects, the villagers were forced to find their own transportation to the site, take with them their own tools and food for the duration of their stay, and work without pay until their allotted section of work was complete. Villages nearest the site were targeted first, but as the project continued, people from further afield were used. The work was overseen by Tatmadaw soldiers, who often beat people considered not to be working hard enough, and there were few safety precautions, so that laborers sometimes died in accidents and landslides. After months of such work, during which time they were no longer able to tend their fields, villagers lost the ability to sustain themselves and had no option but to flee to Thailand....

The other major development project that affected the Mon was the gas pipeline that was to be built to carry natural gas from the Gulf of Martaban across Burma and into Thailand. The original route was to have taken the pipeline to Three Pagodas Pass, though a shorter land route coming out further south at Nat Ei Daung was finally agreed upon. Nevertheless, in preparation for the pipeline, which would be vulnerable to attack by ethnic minority forces, Mon and Karen villages were forced to relocate, and in 1995, the SLORC created a new army command position, the Tenasserim Coastal Military Command, whose headquarters were in Tavoy. The increase in Tatmadaw soldiers in the area led to an immediate increase in the forced recruitment of civilians as porters and as laborers to build new army barracks in the region, and this contributed to refugee outflows from 1994 onwards." (Source: HRW: "The Ethnic Minorities" & "The Mon," September 1998 )

In most cases, whenever forced relocation happens in rural area in Mon State, the commanders who order the villagers to leave their homes do not give the villagers a place they need to move to. Instead they tell the villagers that they can resettle anywhere, as long as it is not in the area of their former village. Some villages are accused of being rebel bases and villagers are suspected of being rebel-supporters. These villagers suffer more than other villagers from torture and killing by the SPDC, and those villagers who are afraid of being killed and tortured try to leave the village.

Sometimes after villagers have been displaced they try to return to their original villages despite the dangers, to harvest cash crops such as betel-nut, and coconut, or to try and cultivate paddy in the fields. When the battalion that ordered them to leave their village is replaced with a new battalion, IDPS are in some cases able to return to their homes, and if the new battalions are less brutal than the previous ones, they can stay longer in their villages. When more brutal battalions come, they flee again. Population displacement is a main problem in southern Burma especially in Karen State, in some part of Mon State and most parts of Tenasserim Division. (Source: HURFOM)

Forced Relocation in Mon State - partial list of incidents 2002

Villagers Flee after SPDC Restrictions on Movement

At the end of January 2002, the commander of LIB No. 550, in retaliation for an

attack made by the MRA, prohibited 200 villagers from traveling to work on their paddy farms or fruit plantations which were outside of the village. The SPDC commander accused all the villagers of being rebel supporters and said that if they did not follow his orders to stay only inside village, he would burn down the whole village.

After this order, many people fled from the village because they were afraid of being killed or tortured. After the SPDC troops left on 30 January, about 30 families with a total of 150 villagers fled to Halockhani Mon refugee resettlement site, which is about 10 Kilometers from their village. The remaining villagers fled to other areas and are currently living as IDPs. (Source: HURFOM)

SPDC Confiscate Land for Artillery Regiment

On 5 November 2002, SPDC Southeast Command confiscated about 200 acres of land from 49 Mon farmers, in order to build an artillery regiment in the southern part of Mudon Township. Most of the land had been used to grow rubber trees, which the farmers had planted several years ago and were waiting to harvest. The owners of the land were Mon villagers from Set-thawe, Do-ma, Kalort-tort and Ah-bit villages. The army did not pay any compensation cost to those who lost their land.

At the same time, some authorities from the forestry department lied to the farmers saying that if the farmers paid them a bribe they wouldn’t lose their land. Since 2000,the Burmese Army has confiscated many thousands of acres of land from Mon farmers in Ye Township. (Source: HURFOM)

13.6 Situation in Sagaing Division

"...In Sagaing Division, the designated administrative boundaries of the division conceal the ethnic diversity within its borders and the internal displacement which has occurred. Many Naga people, estimated to be around 100,000 strong in total, populate the four northern townships of the division, near the town of Khamti and the Patkai mountain range […]. Fighting for an independent Nagaland in both India and Burma, and facing increased internal divisions, the Naga have suffered significant conflict-related displacement.....It is estimated that up to 1,300 villagers have been displaced ….The construction of the Kalay-Gangaw railway line in Sagaing Division illustrates clearly that the problems of forced displacement are not only confined to the war-affected zones. The line crosses mostly flat farmland and paddy fields; these were destroyed without any compensation being paid by the national government." (BERG, September 2000)

Forced Relocation in Tamu Town

On 14 September 2002 Mizzima reported that U Maung Maung Myint, Chairman of the district SPDC division, ordered residents of 38 houses in Block No. 5, Tamu town to vacate their houses before October 2002. The Tamu residents were relocated to Natmyin village to make room for a government project scheduled to start on 15 June. The authorities will disburse no compensation or reimbursement for the expenses incurred during relocation. U Maung Maung Myint further warned local residents that "whoever apprises the BBC or the RFA of the forced relocation plan will be punished severely," reported a local resident. The houses slated for relocation measure 60 inches in length and 80inches in width. One of those facing forced relocation said that he would defy the order and stay at his place. (Source: Mizzima)

13.7 Situation in Shan State

The SPDC has engineered mass forced relocation in Shan state since 1996. This relocation has occured on a scale so massive that many observers conclude that it is intented to permanently change the ethnic composition of Shan state. In 2002 these campaigns continued, often in the name of crop subsitution and drug eradication programs. In 1996 the SLORC delineated a huge area of Central Shan State, and ordered the forced relocation and destruction of every village in the region. The villagers were forced to move into sites more directly under military control. By 1998, over 1,400 villages in 12 townships had been forcibly relocated and destroyed, displacing a population of at least 300,000 people. (Source: Charting the Exodus from Shan State: Patterns of Shan Refugee flow into Northern Chiang Mai Province of Thailand 1997-2002, SHRF May, 2003)

Indicative of the SPDC’s widespread campaign to suppress and ‘Burmanize’ Shan people was Khin Nyunt’s January 2002 response to the ILO’s investigation into the alleged killing of villagers in Kengtung who had complained about forced labor. In his communication to the ILO, Khin Nyunt casually stated that "there were only a few villages in the area" (of Kaeng Tawng), when in fact these villages are relocation sites to which 50-60 formerly thriving villages were forced to move in 1996. Khin Nyunt also denied the existence of several victims because their villages "did not exist" (they had been relocated). Khin Nyunt further corrected SHRF’s use of the Shan name of one village, referring to it by a Burmese name. This village is one of the areas where the regime is now relocating Burmans. In response to Khin Nyunt’s statements, SHRF notes that: "the intent of the SPDC to Burmanize the region, erase the Shan history and identity, and its own crimes in the process, is thus frighteningly apparent." (Source: "SHRF Monthly Report", March, 2002, Shan Human Rights Foundation)

In 1999 SHRF noted, "There are various patterns of displacement for the Shan villagers who have been forcibly relocated from their homes. There are basically four alternatives, which are detailed below. However, many of the displaced have not chosen a single alternative, but have chosen more than one or, in some cases, even tried all four, in different orders. Thus, there are countless variations on the patterns of displacement.

Moving to the Relocation Sites

The term "relocation sites" refers to the sites designated by SPDC troops to which the relocated villagers were forced to move. These were usually areas of bare land near towns, main roads and army bases where nothing at all was provided for them by the local authorities.

Going into Hiding

One option for the villagers ordered to move was simply to go into hiding in the jungles near their villages, and then lead a precarious existence dodging Burma Army patrols while seeking to continue cultivating their crops.

Moving to Towns or Other Areas of Shan State (Outside of Relocation Sites)

Some forcibly relocated villagers moved straight to towns. The main factor influencing whether people did this was either money, which meant that they could afford to purchase land or housing there, or else having relatives in towns with whom they could stay, and perhaps find work. Other people moved to villages on the periphery of the area of forced relocation, which they felt would be safe from relocation because they were under the control of the ceasefire organisations such as the Shan State Army, the Shan State National Army, the Shan Nationalities People’s Liberation Organisation or the Pa-O National Army.

Moving to Thailand

There has long been a pattern of migration of Shans to Thailand to find work, as the historical, ethnic and linguistic connections are very strong. An estimated 150,000 people from Shan state have moved to Thailand since 1996. The overwhelming majority of them come Central Shan state which has borne the brunt of the military’s relocation program. The majority of Shan migrants to Thailand are refugees and their participation in the thai economy is a direct refusal of the Thai government’s refusal to recognize their status as refugees and allow them to establish refugee camps. (Source: SHRF 2003)

The Cause of Migration

Four Shan familes arrived on the Thai border in March/April 2002 from a village in Murg Nai township. These people reported that continuing forced relocation campaigns by SPDC troops have had a severe impact on villages in remote areas. People living close to towns or army garrisons were not subjected to forced relocation, but suffered from other hardships. The conditions for people allowed to remain in their villages are not much better than conditions for those who had been relocated. Although these peoples’ homes are intact, their farmlands have been confiscated for the SPDC troops. In addition, these people spend much of their time carrying out forced labor either for the construction of army camps or to tend the army’s fields. Due to inflation of the Burmese currency, the price of household goods has more than doubled, and with no land for cultivation and not much free time to work, local residents live in a state close to starvation. Even if these villagers are able to find time to work, the average daily wage of 400 kyats (about 20 baht), is insufficient to feed their families. When villagers are allowed to farm lands that have been confiscated from them, they are forced to sell 8 out of every 9 baskets of rice to the army at below market price. The Burmese authorities paid them 1,000-2,000 kyats per basket, while the price is 5,000-6,000 kyats at current market rate. Sometimes the authorities do not pay anything for the rice that they ‘buy.’ As conditions continue to deteriorate daily, more people are choosing to try and flee to the border. (Source: Freedom, March & April 2002)

Year Township Number of people resettled

1999-2000 Monghsat 55,000

2000-2001 Mongton 35,000

2001 (rainy season) Tachilek 15,000

TOTAL 105,000

(Source: SHAN November 2001)

Wa Relocation

In April 2002, the Lahu National Development Organization (LNDO) published a report titled "Unsettling Moves: The Wa forced resettlement program in Eastern Shan State." It describes the mass relocation of Wa people from the Wa Substate which borders China, to the Thai-Burma border in Shan state. The report states that:

"…..since the end of 1999, over one quarter of the entire Wa population have been forcibly resettled from their homes near the China border to southern Shan State. Authorized by the Burmese military junta, the United Wa State Party (UWSP) has sent approximately 1 26,000 men, women and children by truck and on foot over 400 kilometres south to the Thai-Burma border.

Both the UWSP and the junta, the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), have officially stated that the mass Wa resettlement program is aimed to eradicate opium production by enabling villagers to grow alternative crops in the more fertile lands of southern Shan State. However, evidence in this report shows that the resettled villagers are planting new opium fields, with the support of SPDC and UWSP officials.

While it is clear that this resettlement program has little to do with drug eradication, the real motives have yet to be confirmed. This report speculates that the UWSP has carried out the program to gain territory and economic advantages from border trade into Thailand and Laos. It is speculated that the SPDC are carrying out their usual divide-and-rule strategy: pitting the UWSP against the Shan resistance in southern Shan State, and using the UWSP as a proxy army against neighbouring countries; not to mention dividing the Wa themselves. Wa sources also state that financial benefits for individual SPDC leaders have facilitated the move.

Whatever the rationale for the resettlement, this report clearly documents the forced nature of the program and the abuses inflicted not only on those resettled but also on the villagers in the south who lost their lands to the new arrivals. The resettled Wa came from six townships in the northern Wa area, as well as inside China’s Yunnan province. Some were given no warning whatsoever before the move, and all were forced to abandon most of their possessions. Most were herded into trucks to travel south, but many were forced to walk through mountains, taking over two months. Some died en route.

On arrival in the south, the villagers were settled mainly around existing villages in the townships of Mong Hsat, Mong Ton and Tachilek, lying opposite Thailand’s Chiang Mai and Chiang Rai provinces. Upon arrival, the villagers were given rice by the UWSP but, unused to the new surroundings, many fell ill. It is estimated that over 4,000 people died, of malaria and other diseases, during the year 2000 alone.

The lives of the original inhabitants of these areas, mainly Shan, Lahu and Akha, have been gravely disrupted. Their lands and property have been seized by the newcomers, and they have had to face abuses committed by both SPDC and UWSP troops. This report estimates that the number of original inhabitants affected by the resettlement program is approximately 48,000. Of these, it is estimated that at least 4,500 have fled to other areas of Shan State, while another 4,000 have fled to Thailand. These Shan, Lahu and Akha villagers have no access to refugee camps where they can access protection and humanitarian assistance." (Source: LNDO 2003)

Forced Relocation in Shan State - partial list of incidents 2002

Wa Development Project

The remaining villagers in a Thai crop replacement project site at Yawng-kha in Monghsat township across from Chiangrai were ordered to vacate the area.

"Soon after the Thais (in the survey team) left on 28 January, (2002) the Wa began erecting stakes attached with red cloth to mark the outline of what we think is the project site," said one villager who fled to Tachilek, opposite Maesai of Chiangrai province. "They also told us to sell our places and leave because we wouldn’t be allowed to stay there anymore anyway."

The Yawng-kha area, known as Nayao to native villagers, used to have more than 240 households of Shans, Akha and Palaungs, according to a local Shan relief agency but only about 60 were left. The vacated land was filled up by thousands of Wa newcomers, it said. The drive for a Thai-initiated crop replacement project began in earnest soon after Gen Khin Nyunt’s landmark visit in September. Meanwhile, troop movements have been reported from Tachilek to the Yawng-kha area where hundreds of Burmese-Wa forces face the Kengtung Front Force of the Shan State Army at Loi Kawwan. Chiangrai’s local FM radio has also been warning Thai citizens against crossing the border at this time. The battle of Loi Kawwan that was launched against the SSA on 5 February 2001 escalated into a Thai-Burmese border conflict when the nearby Pangnoon Thai outpost was taken by the Burmese forces. (Source: S.H.A.N.)

Villagers Told to Return to Relocated Village in Kun-Hing.

In early 2002, villagers from Saai Khaao village in Saai Khaao village tract, Kun-Hing township, (who had been forced to relocate to the outskirts of Kun-Hing town in 1996-97 by the Burmese army troops), were told by SPDC troops from Kun-Hing-based IB246 to return to Saai Khaao village. When the villagers returned to Saai Khaao village they were forced to stay within restricted areas provide the military with free labour.

Saai Khaao village was the site of one of the most gruesome massacres of innocent villagers committed on 16 June 1997 by the Burmese army troops. On that day, about 60 IDPs were killed at Saai Khaao village and Taad Pha Ho waterfall.These villagers had been forced to move to a relocation site, but then were given permission by SLORC troops to retrieve the rice they had left at their original villages. However the villagers were stopped when they were returning to the relocation site with 40-50 ox-cart-loads of rice and shot dead in groups by SLORC troops. Their ox-carts were then burned and destroyed.

By 4 March 2002, about 68 familes, comprising a total of 345 people, had gone back to Saai Khaao village. Burmese military authorities in the area set up an outpost camp at the village and issued an order requiring the villagers to do the following things:

1. To grow teak trees on both sides of the main road from Kun-Hing town up to Kaeng Tawng area in Murng-Nai township;

2. To build fences around the village, about 4 elbow-lengths in height;

3. Each household to grow 20 mango and 5 jackfruit trees;

4. Each house to dig a ditch in front of the house, 3 elbow-lengths deep, 2 elbow-lengths wide and 10-15 arm-spans long;

5. Every household to take turns to cultivate the 5-acre mango orchard of the military;

6. No villagers to go beyond 2-3 miles from the village to farm;

7. All villagers to stay in their respective house-compounds between 6 pm to 6 am; anyone found outside their compounds within that time would be shot on sight.

8. Each household to raise at least 2 pigs, of which 1 was for the military, and take all the responsibilities, including buying and feeding them, etc., until they were big enough to be eaten;

9. Each household to raise 10 chickens, of which 5 were for the military, and take all the responsibilities, including buying and feeding them, etc., until they were big enough to be eaten;

10. Any one who refused to comply with this order would be fined 5,000 Kyat and punished with 3 years in jail.

The villagers who have left Kun-Hing relocation site and returned to their original village, Saai Khaao, are now facing even more difficult conditions and are secretly, little by little, fleeing to other places. While having to serve the military with forced labour, the villagers continue to be subjected to arbitrary killing and rape. In February 2002, 3 villagers from Saai Khaao village, who were going to their farm were seized by a passing SPDC military column and later raped and killed. (Source: SHRF)

Villagers Forced to Relocate for Second Time

On 14 April 2002, an SPDC army brigade commander ordered his troops to

search the houses and farm huts in every village in Naa Poy village tract, Lai Kha township. After searching and confiscating the villagers’ property, the brigade commander then summoned all the village headmen and said, "Who gave you the permission to return to your old villages? You must resettle along the motor-road-side within 15 days after which all these villages will be burned down". The villagers, who had just returned to their old villages before the cultivation season, then had to move for the second time. (Source: Freedom, May 2002)

Confiscation of Cultivated Land and Repeated Relocation of Displaced Villagers in Nam-Zarng and Lai-Kha.

In June 2002, displaced villagers from Kho Lam village relocation site in Nam-Zarng township who had earlier been permitted by local SPDC troops to return to their original villages, were forced back to Kho Lam by SPDC troops from different units. In addition, the villagers’ and farms were confiscated and given to the Lahu people’s militia.

In March 2002, displaced villagers originally from Ton Hung Haai Laai village tract in Nam-Zarng township and Naa Poi village tract in Lai-Kha township (which had been forcibly relocated to Kho Lam in 1996-97 by the then SLORC troops) were permitted by the present local SPDC troops to return to stay and farm their lands at their original villages. Since then, many displaced villagers had returned to cultivate their lands at their original villages.

The villagers had been staying and working at their original villages for almost 2 months — many had already put up new fences around their old compounds and prepared their lands for growing crops, and some had already planted rice — when a column of SPDC troops from the adjacent Wan Zing village tract in Kae-See township came to Naa Poi village tract area. The SPDC troops brought with them some members of the Lahu people’s militia. When they saw the villagers who had returned to Naa Poi village tract, the troops ordered them to go back to Kho Lam relocation site in Nam-Zarng township, giving them 10 days to move their belongings.

A different group of SPDC troops from Kho Lam also came to Ton Hung Haai Laai village tract and ordered the villagers who had returned to go back to Kho Lam relocation site. These troops accused the villagers of having returned without permission and threatened that they would shoot at anyone found in the area next time they came to the area.

The SPDC troops from Kae-See also told the villagers that their farm lands had been given to members of the Lahu people’s militia because they were helping in the work of the Burmese army, and if Lahu militia were attacked by Shan soldiers after they had come to stay on the lands, the villagers would be held responsible. The Shan villagers had no choice but to return to Kho Lam relocation site, to face a life even harder and more destitute then before. (Source: SHRF)

Shan Teak Houses for Burmese Resettlers

In September newly arrived Shan refugees in Thailand report that a village in southern Shan State whose residents were relocated by the Burmese military during the 1996 - 98 forced relocation campaign has recently been opened for resettlement to arrivals from central Burma proper. "I couldn’t bear to stay there and watch outlanders living in my home while my family had to struggle each day just to survive", said a former native of Nayok Village, Nawng-hee Tract, Kengtawng Township. (Kengtawng, formerly part of Mongnai Township, was named a separate township last month, said migrants from the area.) "So we decided to leave".

Nayok, comprising 47 households, used to be a thriving hamlet and was known for its delicious loganberries. There are 22 houses, 5 two-storied and 17 one-storied, built entirely of teakwood, according to its former occupants, half of whom are already in Thailand."When the Kengtawng urbanization project was announced two years ago, we went back to apply for permission to return to our homes but were rejected," added another one. "The trouble with us Shans is that most of us don’t have any official document to show we own the place, because we were never given any since the day of Zaofahs (Shan ruling princes)."

Rangoon’s massive eviction program had uprooted 99 villages, consisting of 3,850 households in the area, according to Dispossessed: Forced Relocation and Extrajudicial Killings in Shan State by Shan Human Rights Foundation, April 1998.

Kengtawng had been slated for resettlement of 3,000 families coming up from Burma proper, according to the sources. "So far about 500 have already been resettled there," said one. It is also known for its teakwood forests. Asia World, owned by Law Hsinghan, and Shan State South, owned by Mahaja, are two of the firms that have been granted logging concessions in the area by Rangoon.

"One piece of good news is that forced labor in Kengtawng has lessened since the ILO row over last year’s killings of 7 villagers (who complained to authorities of the existence of forced labor despite official banning)," said one. "But we would be happier if we were given back our lands and homes." (Source: SHAN, 22 September 2002)

Displaced Farmers Beaten, Their Land and Property Confiscated and Driven Away in Murng-ton.

In October, 2 displaced farmers were arrested, beaten and detained by SPDC troops from LIB519. The farmers were later forced to leave their land and houses, which were also confiscated, at Wan Naa village about 1-2 miles from Murng-Ton town. These farmers were originally from Naa Khaa Awn village,Ngaa Teng village tract, in Kaeng Kham area of Kun-Hing township, which had been forcibly relocated in 1997 by the then SLORC (State Law and Order Restoration Council) troops. The farmers did not go to the relocation site but came to Thailand instead.

Zaai Aw, (m, 42) the head of the family, reports that after working in Thailand for 3 years, the family members managed to save up some money and return to Shan State where they bought a small plot of land, consisting of a small house and a vegetable garden, at Wan Naa village near Murng-Ton town in Murng-Ton township. After they had stayed at Wan Naa village for over a year, SPDC troops from LIB519 came and arrested Zaai Aw’s son and Zaai Aw’s younger brother and took them to the military camp.

The SPDC soldiers accused Ai Ta, aged 20, Zaai Aw’s son and Zaai Laek, aged 35, Zaai Aw’s younger brother, of being members of the Shan resistance and of having led Shan soldiers to shot at SPDC soldiers. The SPDC soldiers severely beat the two men until their heads were fractured and bleeding, and then locked them up in the camp. The next morning, Zaai Aw and the village leaders went to the military camp and pleaded for the release of Ai Ta and Zaai Laek. Zaai Aw and the village leaders assured the soldiers that the two men did not have any connections with the Shan resistance.

The SPDC troops then told the village leaders that if these people were originally from Kaeng Kham (in Kun-Hing township), they were bad people and must be driven away, and their land would be taken by the military. On 23 October 2002, the SPDC troops from LIB519 actually came and forced Zaai Aw and his family to leave their house and land immediately and banned them from taking anything away. Because they had no choice, Zaai Aw and his wife, their 2 sons and Zaai Aw’s younger brother, once again fled to Thailand. (Source: SHRF)

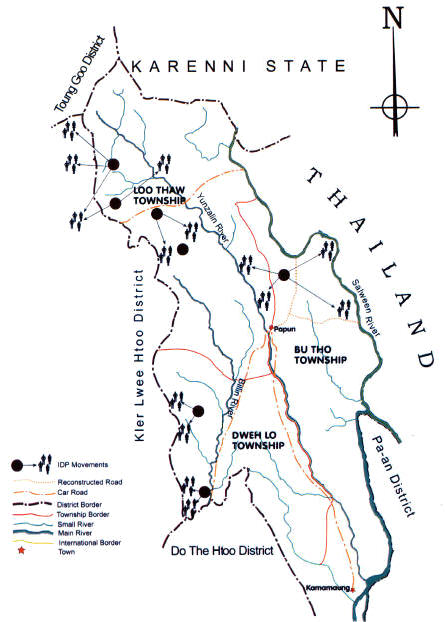

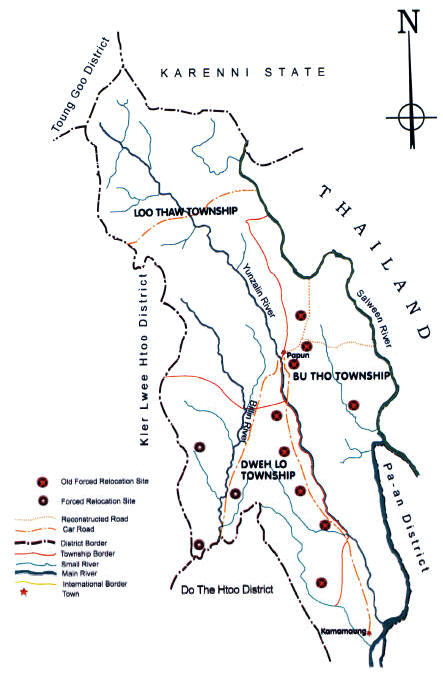

13.8 Situation in Karen State

"While the world welcomed the release of pro-democracy leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi on 6th May, the Burmese military were attacking villages in Eu Tu Klo, Karen State. According to the Committee for the Internally Displaced Karen People (CIDKP), the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) troops burnt down a hospital, a workshop for the handicapped, a school and seven houses. Around 500 people from Pau Kar Der internally displaced persons (IDP) village and Kho Kay village were forced to flee to Thailand.

The 1 to 2 million IDPs, who are eking out a fragile and uncertain existence in the jungles and mountains of Burma, remain in critical need of food, medical care and education. In the month of March alone, over 30 settlements were reportedly attacked and torched. Saw Day Law, the Secretary of the Karen Refugee Committee, described one of the attacks, "On 2nd March, the SPDC troops came to my home village in Karen State, just a few hours walk from the Thai border. The villagers tried to escape to the forest, taking with them what they could. The military has stepped up cross-border security, making it increasingly dangerous for the ethnic minorities to flee to Thailand. Those caught trying to escape are often summarily executed or tortured and then executed." (Source: CSW 8 May 2002)

Situation in Dooplaya District