REFUGEES

INTERNATIONAL

and

OPEN SOCIETY INSTITUTE

Present

PUSHING

PAST THE DEFINITIONS:

MIGRATION

FROM BURMA TO THAILAND

By

Therese M. Caouette and Mary E, Pack

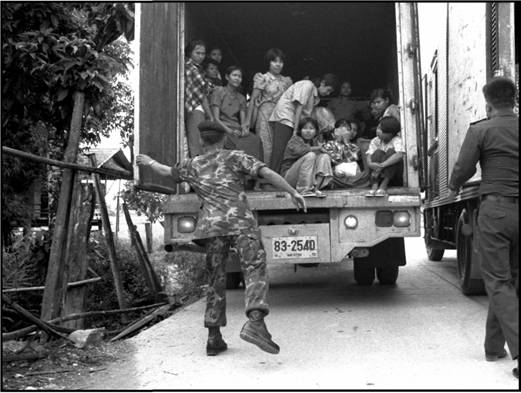

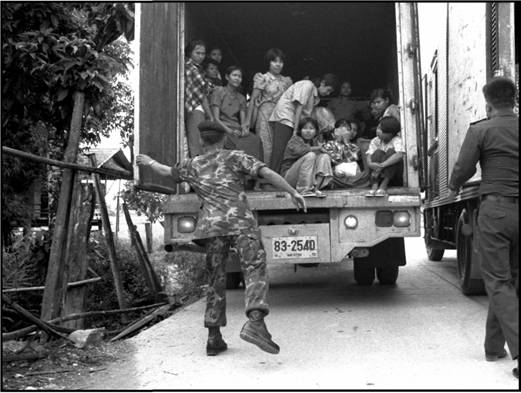

Photo by Nic Dunlop

December 2002

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1

MAP OF BURMA 6

INTRODUCTION 7

I. THAI

GOVERNMENT CLASSIFICATION FOR PEOPLE FROM BURMA

Temporarily

Displaced 7

Students

and Political Dissidents 10

Migrants 11

II. BRIEF

PROFILE OF THE MIGRANTS FROM BURMA 13

III REASONS FOR LEAVING BURMA 15

Forced Relocations and Land Confiscation 15

Forced Labor and Porte ring 18

War and Political Oppression 20

Taxation and Loss of Livelihood 24

Economic Conditions 25

IV.

FEAR OF RETURN 27

V.

RECEPTION CENTERS 31

VI.

CONCLUSION AND

RECOMMENDATIONS 34

For Consideration

by the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC)

of Burma 34

For Consideration by the Royal Thai Government 35

For Consideration by the International Community 36

[Note

by OBL: for this html version: pagination is suppressed and the footnotes have

been converted into endnotes]

________________________________________________________________________________________

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

PUSHING PAST THE DEFINITIONS: MIGRATION

FROM BURMA TO

THAILAND

Recent

estimates indicate that up to two million people from Burma currently reside in

Thailand, reflecting one of the largest migration flows in Southeast Asia. Many

factors contribute to this mass exodus, but

the vast majority of people leaving Burma are clearly fleeing

persecution, fear and human rights abuses. While the initial reasons for

leaving may be expressed in economic terms,

underlying causes surface that explain the realities of their lives in Burma

and their vulnerabilities upon return. Accounts given in Thailand, whether it

be in the border camps, towns, cities, factories or farms, describe instances

of forced relocation and confiscation of land; forced labor and

portering; taxation and loss of livelihood; war and political oppression in

Burma. Many of those who have fled had lived as internally displaced persons in

Burma before crossing the border into Thailand. For most, it is the inability

to survive or find safety in their home country that causes them to leave.

Once in

Thailand, both the Royal Thai Government (RTG) and the international community

have taken to classifying the people from Burma under specific categories that are at best misleading, and in the worst

instances, dangerous. These categories distort the grave circumstances

surrounding this migration by failing to take into account the realities that

have brought people across the border. They also dictate people's legal status

within the country, the level of support and assistance that might be available

to them and the degree of protection afforded them under international

mechanisms. Consequently, most live in fear

of deportation back into the hands of their persecutors or to the

abusive environments from which they fled.

A close

examination will reveal that the definitions used to classify the people from Burma in Thailand are not clear-cut, but in fact,

often blur one into the other. Through interviews that spanned the

course of over two years (May 2000 - September 2002), certain patterns emerged,

depicting who the people are and why they left Burma. In actuality, there is an

arbitrary line between the groups that the Thai government categorizes as

"temporarily displaced," "students and political

dissidents" and "migrants." These faulty distinctions often

result in the vast majority of people being denied asylum and protection and

the superficial identification of millions as simply economic migrants. Hence,

untold numbers of people from Burma are placed at

considerable risk while in Thailand and, if deported, are

often delivered back into environments that are abusive and deny their most

basic rights.

Operating on the

assumption that the majority of those crossing into Thailand from Burma

are doing so only to find employment, the Thai government has sought to

register workers, arresting and deporting those who do not, or cannot, comply.

As of March 2002, 362,082

migrants from Burma were registered to work in Thailand. The registration

scheme includes those working in only eight labor sectors and does not include

people working in the service industry

(including massage or sex work); seasonal workers (those working with an

employee less than one year); market vendors; child workers (less than 18 years

of age); accompanying family members or those who could not pay the 4,450 baht

(US$100) registration fees. The RTG has begun to arrest and deport all migrants

who are not registered and will officially return them to the Burmese

authorities, State Peace and Development

Council (SPDC).

The RTG and

SPDC have officially agreed on a deportation plan with over 19,000 migrants

from Burma arrested and deported between February and May 2002, of which 3,681

were sent directly to the SPDC reception center in Myawaddy, on the Burma side of the border. The reception center is operated

by the Burmese Directorate of the Defense Service Intelligence (DSI) of the

Ministry of Defense and immigrants are interviewed by various SPDC

ministries and departments. In addition, all those repatriated were tested for HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis and sexually

transmitted diseases. Twenty returnees have been identified as positive

for HIV/AIDS and were separated from the others to be sent to a hospital in

Rangoon. To date, no mechanisms are in place to guarantee protection or

monitoring of those returned.

There is an urgent need for the

governments involved and the international community to

recognize the civil war and grave human rights abuses from which the majority

of people from Burma have fled and to stop all deportations until proper

mechanisms are in place to ensure that no individuals having a

credible fear of persecution are returned involuntarily. Mandatory

HIV testing of migrants is a human rights violation and any country or agency currently providing HIV testing

kits should immediately withdraw their support until monitoring and proof of

individual informed and voluntary consent is established.

This

report examines the mixed migration of people from Burma into Thailand and the

ever-blurring nexus between migration and asylum. It provides a discussion of

the classifications assigned to this

population by Thai authorities; a profile of the people; the reasons why they

decide to leave Burma (including discussions on forced relocations and land

confiscation, forced labor and portering, taxation and loss of livelihood, and

war and political oppression and economic conditions); the violence and

security issues they face; and the recent drive to officially return

"illegal migrants" to established reception centers in Burma.

The report concludes with the following recommendations for government

authorities in Burma, the Royal Thai Government and the international

community:

RECOMMENDATIONS

FOR CONSIDERATION BY THE STATE PEACE AND DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL

(SPDC) OF BURMA:

• Implement the recommendations set forth in the

April 2002 resolution of the UN Commission

on Human Rights to ensure full respect for human rights and fundamental

freedoms, including the freedoms of expression, association, movement and assembly, the right to a fair trial by an independent and

impartial judiciary and the protection of the rights of persons belonging to

ethnic and religious group minorities; and to put an end to violations of the right to life and integrity of the human

being, to the practices of torture, abuse of women, forced labor and forced

relocations and to enforced disappearances and summary execution.

•

Repeal SPDC's Law 367/120-(b) (1) that makes it illegal

for Burmese citizens to go to Thailand, sentencing

them to penalties of up to seven years in prison. In addition, amend the

Immigration Act of 1947: (Act 3.2) that makes it illegal for citizens to enter

their own country without a valid Union of Myanmar Passport or a certificate in

lieu thereof, issued by a competent authority. Both these laws violate the

fundamentals of the Human Rights Conventions.

•

Stop mandatory HIV testing of returning migrants.

Mandatory testing is a human rights abuse and against the UN

HIV Principles and Guidelines adopted by member states (including

Thailand

and Burma).

•

Conduct free and voluntary health checks in hospitals and

clinics rather than in the reception centers. It is necessary to

ensure that testing for HIV/AIDS is also provided with

education and counseling in the migrant's language. Strategies should be put in

place for addressing confidentiality, health care needs and issues of

discrimination.

•

Assure that any return to Reception Centers is voluntary

and provides the opportunity for returnees to seek

assistance and services.

•

Accept voluntary returnees without discrimination by

ethnicity or health status.

•

Establish a presence and full access to international

organizations to ensure protection mechanisms on both sides of the border are

upheld.

FOR CONSIDERATION BY THE ROYAL THAI GOVERNMENT:

•

In recognition of the civil war and grave human rights

abuses in Burma,

immediately halt deportations of Burmese pending the establishment of proper

mechanisms to ensure that no individuals having a credible fear of persecution

are returned involuntarily.

•

Establish criteria by which people from Burma may be

granted asylum to include not only those fleeing fighting, but also

those fleeing the effects of civil war and human rights abuses

inflicted by the Burmese regime.

•

Create a task force with representation by governments

and international and non governmental organizations to examine

ways in which protection mechanisms can be put into place prior to

the return of Burmese to the reception centers.

•

Facilitate full access by international organizations

with a protection mandate to establish and ensure that protection

mechanisms on both sides of the border are upheld.

•

Withdraw the National Security Council's martial law

declaring the northern Burma border

areas off-limits to foreign reporters and NGO activists (issued on July 15, 2002).

•

Allow for the establishment of camps inside Thailand

for all ethnicities fleeing Burma,

especially those from Shan State

where the documentation of abuses has been extensive and

the lack of options for asylum has made these individuals particularly

vulnerable.

•

Enhance and streamline the registration process for

Burmese migrants in Thailand to

guarantee basic rights and channels for redress. Provide information to

migrants in their languages on the registration process and on services

throughout Thailand,

as well as Thai policy and implementation procedures.

•

Establish channels for reporting non-compliance and

abuses encountered at the work place by employers and Thai

authorities, and security issues in general. Provide migrants with the same

rights as Thai workers. This would ultimately ensure that the rights of both migrants

and Thai workers are respected.

•

Stop deporting migrants officially to the Burmese

authorities with knowledge that they will be subjected to mandatory HIV

testing.

•

Ensure testing for HIV/AIDS is voluntary and that

communication and counseling are made available in the

migrant's language. Strategies should be put in place for addressing confidentiality,

health care needs and issues of discrimination.

•

Establish monitoring procedures to ensure that mandatory

pregnancy testing is not used as a condition for registration of female

migrants and ensure that employers do not dismiss pregnant females,

but provide maternity leave and benefits according to Thai law.

•

Honor the commitment of the Royal Thai Government to the

Convention on the Rights of the Child to ensure the security and

rights of children, including their right to protection, basic education and

health care.

FOR CONSIDERATION BY THE INTERNATIONAL

COMMUNITY:

•

Advocate ending all arrests and deportations of people

from Burma

until proper mechanisms are in place to ensure that no individuals

having a credible fear of

persecution are returned involuntarily.

•

In accordance with Goal 2, of UNHCR's Agenda for

Protection, which aims at "[p]rotecting refugees within

broader migration movements," UNHCR should

immediately seek to improve its ability to identify people from Burma

in Thailand

in need of asylum and protection, recognizing that many

among those referred to as "migrants" may have legitimate claims to

refugee status.

•

UNHCR should negotiate with the Royal Thai Government to

allow the agency to carry out its protection mandate by expanding

the agency's role in a status determination process and ensuring

access to refugee camps for those from Burma

with a well-founded fear of persecution.

•

Call on the Thai government to grant asylum to those

fleeing Burma,

recognizing the denial of their civil and political rights and calling

attention to the associated denials of their economic, social and

cultural rights.

•

Ensure that the protection and security for all those

returned to Burma

be a priority for any and all international and non-governmental organizations

involved in the process. Donors should require such organizations to operate only

with full transparency and unhindered access to these populations.

•

Any country or agency currently providing HIV testing

kits should immediately withdraw their support until there is proof that no

mandatory testing is being conducted by the government of Burma,

and access to monitoring can be guaranteed.

•

Provide health services and education, including

HIV/AIDS awareness, to the people from Burma in

Thailand in

languages and media that they can understand and access.

PUSHING PAST THE DEFINITIONS: MIGRATION

FROM BURMA TO THAILAND

Recent

estimates indicate that up to two million people from Burma currently reside in

Thailand,1 reflecting one of the

largest migration flows in Southeast Asia. Both the Royal Thai Government

and the international community have taken to classifying this population under

specific categories that are at best misleading, and in the worst instances,

dangerous. These categories gravely distort the situation by failing to take

into account the underlying reasons behind

this migration and to accurately reflect the realities that have brought

so many people across the border. They also dictate people's legal status

within the country, the level of support and assistance that might be available

to them and the degree of protection afforded them under international

mechanisms. Consequently, many people live in fear of deportation back into the

hands of their persecutors or to the abusive environments from which they fled.

A close

examination will reveal that the definitions used to classify the people from

Burma in Thailand are not clear-cut, but in fact, often blur one into the

other. Through interviews that spanned the course of over two years (May 2000 -

September 2002), certain patterns emerged, illustrating who the people are and

why they left Burma. Indeed, there is an arbitrary line between the groups that

have been designated "temporarily

displaced," "students and political dissidents" and

"migrants." These faulty distinctions often result in the vast

majority of these people being denied asylum and protection and the superficial

identification of millions as simply migrants seeking work.

I. THAI GOVERMENT CLASSIFICATIONS FOR PEOPLE FROM BURMA

Temporarily Displaced

Over 138,000

people currently reside in thirteen camps scattered along the Thai/Burma border.2 Although

commonly referred to as "refugees," the government of Thailand

prefers to officially identify them as "temporarily displaced."3

Those allowed to enter the camps are primarily ethnic Karen and Karenni whom the Thais

have determined were "fleeing

fighting" when they left Burma.

This narrow definition excludes many people of different ethnicities who also have been

caught in the civil war and forced to leave their homeland as a result of human rights abuses and various other forms of

persecution. As a result, large groups of asylum seekers remain on the

Burma side of the border unable to gain access to the camps in Thailand, but

also unable to return to their home villages. According to numerous reports by

relief workers and other organizations, as many as 600,000 to 1,000,000 people are estimated to be internally displaced

inside Burma. Many of those who have made their way into Thailand and have been

interviewed through the Thai government

screening process, have been denied access to the

camps and are slated for deportation.

Instances of 'push-backs' or forced returns of both those rejected by the screening

process and those not yet interviewed by the screening board have been reported.4

The Thai

government screening process is a relatively recent exercise - instituted only

four years ago (1998) with the establishment of Provincial Admissions Boards.

Previous to that, no standardized, formal status determination process existed

and entry to the amps often depended upon

the discretion of provincial and camp officials.5 Many

of the camp residents were even allowed to work outside the camps in nearby

towns and farms. As the Thai government has improved its relations with

the Burmese generals in Rangoon, however, it has tightened its policy toward

the displaced from Burma and has begun

restricting movement in and out of the camps.6 It has also strictly

adhered to its "fleeing from fighting" criteria for granting asylum,

thereby severely limiting the number of those officially admitted to the

country. From the period of May 1999 through December 2001, 29,067 persons

applied for asylum in Thailand. Of those, 41 percent (11,718) were accepted and

35 percent (10,408) rejected. The remaining 24 percent (6,941) were still awaiting consideration by the Provincial Admissions

Board.7 The process, for the most part, has ground to a halt,

however, as the Provincial Admissions Board

has not met for nearly a year.

In

addition to the limitations imposed by its restrictive screening criteria, the

RTG has continued its reluctance to consider among its pool of

"temporarily displaced," other ethnic populations beyond the Karen

and Karenni. For example, despite the visible fighting along the Thai-Burma

border during May and June 2002, with the arrival of at least 1,500 people from Shan State

into Thailand,8 the plea of this

population for aid and protection

has been ignored. The Shan, Akha, Lahu, Wa, Kachin and other minority populations have yet to be considered as

"temporarily displaced" persons, leaving them no option but to

be absorbed into the local communities and to seek work for their survival.

This policy persists amidst continued reports of fighting, forced relocation,

widespread rape as a weapon of war and other forms of torture and human rights abuses.9

Also in

1998, the Thai government invited the United Nations High Commissioner for

Refugees (UNHCR) to establish offices in three provincial towns and to act as

observers to the screening process and register those in the camps, marking the

first time the UN agency would have a

presence along the Thai-Burma border. It was hoped by many that a UNHCR

presence would significantly enhance the protection of asylum seekers from Burma, both with regard to the granting of asylum

and the issue of security in and around the camps. From the onset,

however, the limited role allotted the UN agency by the Thai government raised concerns.

At the

time UNHCR was allowed to set up its provincial offices, the agency and others

believed that the Thai government was also agreeable to broadening its very

limited criteria for granting asylum to

include, not only those 'fleeing fighting,' but also those fleeing the

'effects' of fighting and civil war. To date, this change has not occurred. Maintaining this very

restrictive admissions criterion has meant that thousands of asylum seekers

have been denied admittance by the Provincial Admissions Board over the past

five years. The relegation of UNHCR to "observer" status in the

admissions screening has restricted the agency's ability to significantly

affect the process. UNHCR has appealed many cases and has had some limited

success, but the decisions on the vast majority of cases deemed ineligible by

the RTG have not been overturned.

With

regard to its own status determination procedures, UNHCR faces a multitude of constraints. The agency does continue to conduct

some interviews in Bangkok and issue letters indicating that an asylum seeker

has been designated a "Person of Concern." The reality is,

however, that only a small fraction of those fleeing Burma because of

persecution and abuse by the Burmese authorities has the opportunity to present

their cases to UNHCR or to access protection by the agency.

Students and Political

Dissidents

This

category is reserved for students and political activists who fled Burma

following the crackdown of the pro-democracy movement by the Burmese military

in 1988. The majority of those accepted into this category were among the

nearly ten thousand people who flooded into Thailand following the '88

uprisings, first to the jungles along the border

and later making their way to Bangkok. The Thai government allowed UNHCR to register

these individuals and provide them with some financial support. Because of political sensitivities, however, UNHCR used the

term "Person of Concern" (POC) rather than "refugee"

for the displaced students and dissidents, even though individual status determination procedures followed the traditional

refugee criteria set by the agency.10 Only those who could

prove that they were involved in the 1988 demonstrations and made their way to Bangkok were granted 'Person of

Concern' status. Those who remained at the border or could not provide

the required proof were denied any recognition of the need for asylum, leaving

them technically illegal in Thailand and subject

to intimidation, arrest and deportation.

In 1992, the Thai Ministry of Interior established a

'safe area' at the Maneeloy Center in Ratachaburi province to house all the

'students.' From the Center, students could apply for

resettlement abroad. Many students and dissidents chose not to enter Maneeloy,

either because

they feared reprisals against them or family members inside Burma if they

officially acknowledged their participation in the pro-democracy demonstrations

or because they wanted to continue their lives and political activities freely

in Thailand. Many also believed that the

'safe area' was merely a venue from which the Thai government could

easily repatriate the students if and when it might be politically expedient.

Over the

next several years, however, life became increasingly difficult for students in

Bangkok and at the border. Although they did not originally intend to enter the

labor force, many students and dissidents

worked in a variety of jobs (such as in factories or at construction

sites) in order to survive. All too often the students, including those who were registered with UNHCR and had 'Person of

Concern' status, were treated no differently from migrant workers or

tourists who had overstayed their visas. They could be arrested, sent to

immigration detentions centers and/or deported with other illegal migrants.11 Ironically, many students

actually preferred not to identify themselves as POC when they were

arrested because doing so would often lengthen their time in the detention

centers. Whereas migrants were routinely deported to border sites where they

could bribe officials and make

their way back into Bangkok,

POCs were often subject to prolonged detention while immigration authorities considered

how to handle their

cases.12

By the late

1990s, many more political dissidents (including former students) began to register with UNHCR in an effort to gain at least

the minimal recognition of 'Person of Concern' status and enter Maneeloy

Center to explore the option of resettling in a third country. As of 1998,

2,231 students were registered with UNHCR, and of those 1,641 were resettled overseas.13 In

addition, a growing number of recently released political prisoners from inside

Burma began arriving in Thailand seeking refuge from harassment and fear

of further persecution for their political beliefs. Despite having suffered

this most extreme form of persecution,

however, only one former political prisoner is known to have been

accepted by UNHCR as a 'Person of Concern' at the time of the writing of this report.14

After a

group of Burmese students seized the Burmese Embassy in Bangkok in October

1999, the Thai government demanded that any students remaining outside of

Maneeloy report to the Center immediately and actively sought to facilitate

their resettlement abroad. By December of that year, 2,905 students had

registered and entered Maneeloy. Due to the increasing difficulties of

'living-at-large' in Thailand, hundreds more went to live in Maneeloy 'illegally,' without having registered with UNHCR or

the Ministry of Interior. Almost all registered residents were resettled

in third countries by the time Maneeloy closed in December 2001. The nearly 400

registered persons who remained were

transferred to Tham Hin camp closer to the Thai/Burma border. The fate of those

in the Center who were not registered at the time of its closing is less

apparent. It is assumed, however, that most of them filtered back to Bangkok or

border towns, once again becoming part of the gray pool of illegal migrants.

Still to date, the only way for political dissidents to

seek asylum in Thailand is to apply in person at UNHCR offices and wait,

sometimes for months, for an interview and the status determination procedure

to play out. Throughout this process, most are left to join the masses of

migrant workers from Burma throughout Thailand in order to survive. Often even those who are accepted as 'Persons of

Concern' must continue working along with other migrants to cover their daily living expenses.

Migrants

"Migrants" is the category used to identify an

estimated two million people from Burma currently on Thai soil. A number of factors have

contributed to this massive influx of people, including ongoing civil war,

political upheaval and brutal repression that followed the 1988 democracy

demonstrations. This occurred at the same time Thailand was experiencing the

economic boom of the late 1980s and found itself in dire need of unskilled labor, which the people from Burma

could provide. Pressure from the business

community moved the Thai

government to pass a series of four Cabinet resolutions between 1992 and 1999 that temporarily allowed employment of migrants

in various sectors of the economy.

The 1992

Cabinet Resolution was the first step in expanding the foreign migrant labor

force by allowing the employment of displaced persons or illegal migrants from

Burma. Restricted to migrants in only nine

border provinces and requiring a 5,000 baht15 fee from the

potential employers, the registration that followed the resolution was

completely unsuccessful (only 706 aliens registered). Employers chose instead

to continue hiring illegal workers by

paying off local officials.16

A

subsequent resolution in 1996 expanded the pool of workers by allowing migrants

from Burma, Laos and Cambodia to be registered. It also expanded the number of provinces where they could work from nine to

forty-three,17 but limited the types of industries

that could employ migrants to eight. Most importantly, the resolution lowered the fee required from employers to register their

workers. As a result, between September 1, 1996 and May 22, 1997, a

total of 303,088 migrants were granted work permits. Of these, 263,782 (87 percent) were from Burma.18

In

response to the Asian economic crisis in 1997 and the rampant unemployment that

followed, the Thai government decided that jobs held by foreign migrants should

go to Thai workers. Under the April 1998

Cabinet Resolution, 300,000 Thais were to be hired in place of migrant

workers. This backfired, however, as few Thai workers wanted the jobs that the

migrants had previously held. Subsequently, the Royal Thai Government passed a resolution in May that allowed a limited

number of migrants (158,253) to work for

one year.19

As work permits issued in 1998 were about to expire, the

Cabinet passed a new resolution in August of 1999 that allowed migrants to be

employed in areas of the workforce where Thai replacements were not available. A significant

policy change within this resolution was that each province could determine for

itself in which sectors the migrant labor was needed. It was during this period

too - particularly after Burmese students seized the Burmese Embassy in Bangkok

on October 1, 1999 - that the Thai government beefed up its deportations of people from Burma without documentation. In the

month that followed the registration deadline set out in this

resolution, a massive crackdown led to a series of deportations. From November

1, 1999 through December 6, 1999, 75,315 migrants were deported, of whom 70,835 were from Burma.20

The

most recent Thai government initiative, from October to November 2001, resulted

in 447,093 persons being registered in ten labor sectors.21 The majority were workers in agriculture (99,149), fishing

(77,714), and domestic services (59,873), with an additional 19,600 "laborers

without employer." The registration scheme did not include migrants

working in many other sectors, such as the service industry (including massage

or sex work), seasonal workers (those working with an employee less than one

year), market vendors, child workers (less than 18 years of age), other family

members or those who could not pay the

4,450 baht (US$100) registration fees. Many migrants failed to register because

they were not informed (or were ill-informed), could not travel to the

registration sites, had become confused by the various work permits and

processes introduced or their employers

refused to participate.22 As will be discussed later, for the

majority of migrants, the

registration process increased their dependence on their employer not only to

register, but also to maintain their "legal status." In

addition, it is reported that employers consistently

keep their workers' registration cards, limiting migrants' autonomy and ability to prove their legal status.

The

October-November 2001 registration was valid for six months, with an additional

six-month extension contingent on migrants obtaining and passing a health

check-up. Health tests were given until March 2002. A total of 448,480

registered migrants underwent the health

tests, of whom 62,082 were from Burma.

A total of 5,305 foreign migrants were found with at least one of eight

diseases tested and will be deported back to Burma.23 The majority of migrants were brought to the health centers

by their employers

and many, fearing the repercussions, did not return to obtain their results.

II. BRIEF PROFILE OF THE

MIGRANTS FROM BURMA

Mobility and cross-border migration within and from

Burma into neighboring countries has been increasing rapidly over the past

decade.24 The number of people moving into Thailand has been

growing consistently since 1988 with only a temporary decrease recorded in

1999, following Thai government crackdowns, arrests and deportations of undocumented migrants back to Burma.25

By the year 2000, the number of migrants recognized by Thai Government

officials reached two million, nearly double its 1998 estimates.26

The majority of those identified as migrants entering Thailand

from Burma

are fleeing civil war, political persecution and/or social, economic

and cultural abuses.27 For most,

the various types of human rights

violations are intertwined and impossible to separate. Often times, the first

move for those facing abuses at home is to relocate within Burma and stay nearby their home and farmland. However,

many find it impossible to survive on the limited available resources

while facing ongoing harassment and denial of their basic rights. Finally,

often as a last resort or in desperation, the decision is made to cross the border into Thailand.28 A clear

example of this is the well-documented, massive forced relocations of

Shan villages since 1996, involving over 300,000 people which continues to date

amidst new waves of forced resettlement involving nearly 126,000 people from Wa-controlled areas along the China border to the

Eastern Shan State.29

The people from Burma in Thailand not only come from

Thai border areas, but also from the Delta region of Central Burma and as far

away as Northern Shan and Kachin States (bordering China) and Arakan and

Rakhine States (along the borders of Bangladesh and India).30 The migrants, who are from ethnically diverse

groups, often do not have a common culture and are unable to communicate

in a common language among themselves or with Thai nationals. Though there is

no known data on the ethnic breakdown of migrants from Burma in Thailand, the

majority are Bamar, Shan, Karen, Karenni and Mon. The majority of migrants have

limited or no formal education and, although they can speak several languages

they are often illiterate. The illiteracy rate is particularly high for female and young migrants.31

Migrants

from Burma in Thailand are of all ages and family compositions. Employed

migrants are typically between the ages of 14 and 40. There is a greater demand

for adolescent and young adult migrants and,

increasingly, for female workers.32 Families often send a

young family member to Thailand or deeper into the country (from the border

areas) to find work and support the family. Not only are the migrants undocumented and thus considered illegal,33

but much of the work they find is itself considered illegal such as sex work,

begging, logging and trafficking in drugs or humans. For example, it is

estimated that nearly 350,000 young children from Burma have been recruited as workers, predominantly into begging

rackets in urban areas of Thailand.34

All

people from Burma in Thailand live in fear of arrest, detention and deportation

back across the border. At the time of

writing this report, even registered migrants are awaiting news of the

Thai government's decision to extend their work permits (which expire on August 28, 2002),

under what conditions and if their employers will be willing to reregister

them.

Most

migrants from Burma are willing to pay large sums in bribes to Thai officials

to avoid arrest, detention and deportation.

Their fear, however, has been heightened with the agreement between the

Thai and Burmese authorities to begin official repatriations of migrants

directly to recently established Burmese

government-run reception centers just across the border. The reception centers

run by Burma's Ministry of Defense require migrants to provide detailed

background information to various ministries and departments of the State Peace

and Development Council (SPDC). Migrants fear this process will result in their persecution, given the laws and decrees in

Burma to arrest and detain those who illegally leave the country, as

well as potentially mark them as a dissident. The reception centers also demand

health check-ups for all returnees that include testing for HIV/AIDS. To date,

twenty migrants, who tested HIV positive, were separated from others and said to have been taken to a hospital in

Rangoon. In addition to the government requirements at the reception

centers, there are the ongoing fears of persecution and human rights abuses

from which many originally fled.

III. REASONS FOR LEAVING BURMA

Although once in Thailand,

people from Burma

are classified under one of the categories discussed earlier, the majority will

have entered Thailand

for remarkably similar reasons. Interviews with the 'temporarily

displaced', 'students and political dissidents,' and 'migrants' reveal that

regardless of their classifications in Thailand, the vast majority has

experienced a life of persecution, fear and abuse in Burma. While the initial

reason for leaving may be expressed in economic terms, underlying causes

surface that further explain their realities while living in Burma and their

vulnerabilities upon return. Accounts given

in the border camps, in towns and cities, factories and farms in Thailand, describe

instances of forced relocation and confiscation of land; forced labor and

portering; taxation and loss of livelihood; war and political oppression in

Burma. For most, it is the inability to survive in Burma that causes them to

come to Thailand.

Forced Relocations and

Land Confiscation

A significant portion of the migrant population in

Thailand comes from inside Shan State. The Shan, like many other ethnic groups, are

categorically regarded by the Thai government

as illegal migrants. They can be found working in various sectors of the Thai economy,

but primarily in agriculture, fishing, construction, domestic and factory work.

The year

1996 marked the beginning of a systematic program of forced relocations in Shan

State carried out by the Burmese authorities in an attempt to cut off support

to the Shan resistance. In a six-month

period alone (March-September 1996), over 450 villages in the area between

Namsan-Kurng and Heng-Mong Nai had been forced into relocation

sites, affecting an estimated

80,000. Forced relocations continued in 1997 in other areas of Shan state. Many

who had been relocated the year before were once again forced to move. By 1998, over 300,000 people had been

affected by the relocations.35 The numbers fleeing into Thailand

have only increased since then and include not only Shan, but many other smaller minority

populations dispersed among them. It is now estimated that some 425,000 people from Shan State have been uprooted

and have fled to Thailand.36

In

December 1996, there were over 60 households in my former village and we all

had to move. People had fired bombs into the village. The villagers scattered.

My family left our paddy in the field when it was ripe enough to harvest, just leaving it all behind. When we moved we took only

a few clothes and walked three days on foot. Then we walked two more

days to another township and stayed there.

We worked for whoever employed us. There we stayed with other people, but we

had to have something to eat. The employer didn't tell us how much he would

pay us, he just gave us some rice to eat. If there was

work to do, we had to do until it was done.

We stayed there for two years, before returning to our former villager

in Eastern Shan State. When we returned to our village, it was like we

had come to a new place. Coming back to the village, we worked for others on

our own farms. It was really difficult to earn a living. I stayed for four

years until I came to Thailand

yesterday.

A

40-year-old Shan male interviewed on April 20, 2002, the day after arriving at

the Thai border in Chiangmai Province.

I came to Thailand because there was no

money for planting or for our daily living

expenses. It is difficult to work in our village because the Burmese military

expels us to the towns. We didn't move to the town, but hid in the jungle

instead. Our plants were ready to harvest and all our livestock was there. The

government military burned down our houses and whenever they saw a cow

or buffalo they would shoot it. There was nothing left. They even burned my

sewing machine. We had to ask for dishes from other people. We moved back and

forth from my village to the town because we were not allowed to work on our

land. If other people employed us, I could eat. We kept trying to sneak back to

our farms to work, but we had to be very careful the military didn't see us.

Sometimes we starved for two or three days

when we went back because we were afraid to cook. We were afraid the military

would see the smoke. We tried to cook at noon when the sun was very bright.

A 22-year-old Shan female interviewed on March 24, 2002,

one week after arriving at the Thai border in Chiangmai Province.

On May

5, 2002, eighteen other villagers and myself had to construct a fence for the military outpost

stationed three miles from my home. Each person was ordered to bring with them

two bamboo poles from the village to the outpost as well as their own food. They had to work from 7am to 4pm with only a

break for

lunch. At the outpost, we met about

20 others from another village with many as young as 13 years old

among them. No one was paid.

Later the same month, the village chairman was told the

village had to move one mile away. The place we were to move to was a small plot of

land about 80 x 40 feet. Many other villagers were also forced to relocate to

this area. Many more were still moving to

the new site when I left for Thailand on May 27, 2002. There is no way I

can feed my family on this land and the military issued an order that anyone seen on their old land would be shot to

death.

A 23-year-old Karen female interviewed along the Thai

border on May 29, 2002.

For many, the relocations were just the beginning of a

cycle of moving from place to place, living in forest and jungles, scavenging

for whatever food they could find or grow. They then become part of Burma's

estimated two million internally displaced

persons (IDPs).37 Having no other viable option, these people cross

the border and assume the new mantle of "illegal migrant. "

For example, between 1996 and mid-2001, an estimated 120,000 Shan are believed

to have entered Thailand.38

...We

were relocated from our village about three years ago, because we were accused of helping the resistance. For the first

year we had permission to go back to our village to plant rice. The following

year we could only do it if we gave half our crop to the Burmese. This

year the little bit we could harvest was not enough and we were not allowed to

go foraging. We couldn't survive, so we left....

A

35-year-old Shan man interviewed on June

30, 2002, upon arrival at the Thai border in Chiangrai Province.

People in Shan State are also being

displaced as large numbers of ethnic Wa are being moved from the northern Wa area adjacent to the

border with China to

the Thai border area opposite the towns of Chiang Rai and Chiang Mai. Up

to 250,000 Wa are supposedly slated to be resettled there with the blessing

of the Burmese central government39

and as many as 50,000 to 100,000 have already moved.40 Many of those

who have been uprooted from their land by

the Wa resettlement scheme are making their way into Thailand.

In May, 2000, Refugees International interviewed

several migrant families who had recently come from Shan State and were living in

villages outside of Chiang Doi, Thailand. Even then, the Wa resettlements were driving people from Burma.

...We

are from a village in Myo Maw Az township in southern Shan State. There we were farmers and owned land. Then the Burmese

began selling land to the Wa. On February 9

[2000], our land was taken....

A 39-year-old Lahu man interviewed in May 2000, working

on a farm along the northern Thai border.

More recently, a Shan man described the harassment

currently being inflicted by the Burmese military as well as by the Wa and other groups:

The

Muser [Lahu] and Wa who have taken up guns are making

trouble for people. If they wanted us do something for them, they said that the

Burmese military ordered us to do it. If we didn't do it for them they complained

to the Burmese military and the military

found fault with us. We were not only tortured by the Burmese, but we

were also tortured by the Musers and Wa. The situation

now is like this.

A 40-year-old Shan man interviewed in April 2002, a day

after he arrived along the border in Chiangmai Province, Thailand.

Victims of forced relocations and land confiscation are not exclusive to Shan State

or to those who are labeled as 'migrants' once in Thailand.

During interviews with the 'temporarily displaced,' such as the ethnic Karen

residents of Mae La camp along the Thai-Burma border, numerous accounts of losing

one's land or being forced from one's village

emerged. Like the Shan, many of the Karen had been internally displaced before

making their way to Thailand.

...I am a farmer. Our land was confiscated in 1992.

They [the Burmese army] wanted porter fees and other things too. Then I went to Thi

Khe [a camp for the internally displaced on the Burma side of the border]. I

was there when [the Burmese army] attacked the camp. Seventy households crossed

into Thailand... A Karen man interviewed in

Mae La camp in May 2000, along the border in Tak Province, Thailand.

My

village is located in Karen State. One day, the Burmese military came and burnt down our village. My family had to run to a

village on the Thai side of the border. We don't want to be refugees. We

don't want to leave our house but we have

no choice. My father is now working on a Thai farm and now my mother is sick.

So I had to find a job in a factory in Mae Sot. My family always wants to go back

to Burma, but we don't know where to go back as our village is not there anymore.

A 17-year-old Karen female interviewed on December 17, 2001, after recently arriving at the

Thai border.

Forced Labor and Portering

Perhaps

no other human rights abuse inflicted upon the people of Burma has been as

thoroughly documented as that of forced labor. International bodies such as the

International Labour Organization (ILO), the United Nations High Commissioner

for Human Rights (UNHCHR) and the International Confederation of Free Trade

Unions (ICFTU), as well as numerous human

rights groups, have gathered hundreds of pages of testimony from the

victims of this systemic practice. The ILO has taken action

unprecedented in its eighty-year

history to sanction the Burmese authorities for its continued use of forced

labor.

Just as the experience of forced labor and portering

cuts across ethnic lines, it also cuts across the various classifications of

people as defined by the Thai government. Forced labor has been experienced by thousands,

if not hundreds of thousands, of those now living

in Thailand.

Accounts taken from various ethnic groups throughout

Thailand attest to the prevalence of forced labor and portering carried out by the

Burmese military in Burma. Excerpts from some of the most recent interviews

confirm that the practice is continuing:

I and

four others from my village had to work for the military for three days in January 2002. We had to construct a fence for the

military camp. In April 2002,I had to go again, this

time with 28 other villagers, six of whom were the same age as me. If we did not go we had to pay a fine of

500 kyat41 each. Both times we were not given any food, water or wages. There was no water in the area

and we had not only to carry water for ourselves, but some of the

villagers also had to carry water for the soldiers. There were also prisoner

porters who had to carry things for the

soldiers when they went for operations.

In

June 2001, and twice in April 2002, my father had to go be a porter for the

Burmese soldiers. Two times he had to carry shells for the troops and another

time a sack of rice

transporting a wounded Burmese soldier on his return. Each time he went for two

days bringing his own food and water and sleeping in the

jungle without any means of protection.

A 13-year-old Karen girl interviewed on May 22, 2002, along the Thai border.

We had to clear the road to our village for the

government. It was last year but I don't remember which month. It is still going

on. We have to work for the government but without pay. Once there was a road

to be built near my village and my father

had to go to work with his own lunch and paying his own traveling expenses.

If we cannot work as a porter, we have to pay 1,000 kyat to someone else to go in our place. That is for one day.

They feed people rice and water only, no curry. I had to work as a

porter once and did not get paid anything.

An

unemployed 22-year-old Chin male who arrived in Thailand's Tak Province in January 2002, and

was interviewed ten days later.

I

couldn't do any personal work because I had to do forced labor for many months.

I had to take my own pots and food with me too. We built a road. They forced me

to carry rocks and sand. The people who had an oxcart and car used them to carry rocks and sand. For me, I just carried rocks

and sand into the car for them. I didn't have time to earn a living or

work personally for my family. If

there were two persons in a

family, one person had to go. If there were four persons in a family, two

persons had to go.

A 30-year-old Shan male who had arrived in Thailand on March 25, 2002, and was interviewed the following day

in Chiangmai Province.

In

January 2002, while I was driving our family's ox cart after selling some

produce, I was stopped at the gate of my village by Burmese soldiers. They told

me to carry stones and sand or pay 300

kyats. I did not have enough money, so I quickly borrowed some from my

relatives and gave it to the soldiers. Only then did they set me free with my ox cart.

In

April the soldiers returned requesting 100 persons from our village to go to

work for them or pay 500 kyat each. The place was an hour and a half from the

village each way and everyone had

to carry their own food and water. There is no end to this so my family left

for Thailand.

A 17-year-old Karen female interviewed on May 15, 2002, along the Thai border.

Since

my turn of portering was coming soon, I prepared for it. I paid them 6,000 kyats then I packed my clothes and came to Thailand

right away.

A 40-year-old Shan male arriving at the Thai border on April 19, 2002,

and interviewed

two days later.

We had to volunteer last year to build a road located

about a two hour walk each way from our village. Every household had to provide

one person and we had to go with our own meal. My husband went to work to

make good deed.

A

52-year-old Pa-O female interviewed in December 2002, after having arrived in

Thailand's Tak Province five days earlier.

War and Political

Oppression

Civil war

and brutal suppression of political dissent have forced migration from Burma

for many decades. The realities of the civil war and extensive use of weapons

and landmines by all sides are detailed in the Landmine Monitor: Burma

(Myanmar), by the International Campaign to Ban Landmines. Often the

various militant groups are not distinguishable to the civilian population and,

in addition, the violence often extends to involve

groups protecting their own interests (such as logging and drug trafficking).

The report consistently points out that the most vulnerable victims are

civilians caught in conflict-ridden areas

(primarily ethnic minority communities).42 Since 2000, several thousand

people have crossed into Thailand from Shan State fleeing the fighting between the

Shan State Army, the United Wa State Army and the SPDC. In May and June 2002 alone, over 600 people crossed into Thailand

as a result of the fighting.43 None of these

people have been considered anything but undocumented migrants except by a

handful of small

non-government organizations who provide limited emergency assistance.

Women are particularly vulnerable to violence and

physical abuse in these situations. Rape as a weapon of war is widespread.

Burmese

soldiers raped my sister and tried to rape me while we were collecting firewood

near their base. After that the soldiers told my father that he disgraces them

because of his daughters. The headman of our village was beaten by the

commander for not solving the case - but it was the Burmese commander who raped my sister. After the rape my husband blamed

me too. He said, 'Why didn't you call a man to go with you? Because you

are only women you suffer like this. Because

of this the soldiers come and beat me often.' My husband was taken to do forced

labor more than other men. It is so many times, I lost count. He has been badly beaten nine or ten times. So we decided to

leave.

Within a year's time, a soldier from the battalion that

raped my sister came and shot her dead while she was in the paddy field.

We do not know why, but we believe it was

because of the rape.

A 33-year-old Karenni woman interviewed on September 21, 2002 in

a refugee camp (where she lives with her husband and children), having arrived

in Thailand

in March 1999.

I arrived in Thailand

in March of 2002 with my husband and three children. I had been

wanting

to leave Burma for a long time. My

husband and I suffered abuse and forced labor by the Burmese army while living

in our small village. Soldiers from the army battalion stationed near my

village would come twice a month and recruit my husband for forced labor. They

also recruited women to carry their supplies. Both men and women were beaten by

the soldiers while on forced labor duty.

While I was four months pregnant, the soldiers asked all villagers, including me,

to carry supplies. Although I have done forced labor often, I refused this time

because I was pregnant. Because of this the

soldiers beat me.

The soldiers were very

cruel. One time they asked a 13-year-old to be their guide. Once they were in

the woods outside the village, the soldiers raped her. When she tried

to run away, they shot her. I did not see this, but a soldier later reported

this to the villagers.

The reason that we made plans to leave was because of

the time they tortured my husband. As a result of this beating and

torture, my husband suffers pain to his back and he became crazy. He is terrified

that the soldiers will come to torture him again. He is never at peace. I

worried that I would be tortured next so we decided

to leave the village and come to Thailand.

We really did not want to

come to Thailand. I heard that we would not be welcome

and that the trip was dangerous.

A 29-year-old Karen woman

interviewed in a refugee camp on September 14, 2002 where she resides illegally with her sister's family.

The majority of victims

from Burma's civil war and

political repression have fled to Thailand

where they face life as 'illegal migrants' without any means of seeking protection.

Living in a society that represses any form of political dissent, members of opposition parties and

political activists have faced arrest, imprisonment and death in Burma. While

fleeing to Thailand has often been the only option available to them in order to escape such consequences, these

individuals do not necessarily experience the protection and refuge they

had hope to find.

Reports

of arrest and deportation of people from Burma highlight the dangers of returning migrants without screening procedures

and protection mechanisms in place:

On December 4, 2000, following an invitation to a

two-day religious ceremony at a local church in Bangkok to commemorate the 6th

anniversary of the church, over 150 Burmese from different areas of Bangkok

attended. The church offered those who lived

far away accommodation for the night. At 11 pm that night 20 Thai police arrived and

arrested 105 people from Burma. Following interrogations, 65 were sent to the Wan Toon Lan police station and 32 were sent to the Chook Chai Si police station. All were

charged as 'illegal immigrants.' On December 5, all were sent to the

Bangkok Immigration Detention Center and the following day sent to the Mae Sot

detention center. On the morning of December 7th

all were sent to Myawaddy by boat. The Burmese Military Intelligence met the boat

and immediately identified three political activists: Khaing Kaung Sann, the chairman of the Rakhine Patriotic Literature Club;

Ko That Naing, a member of the Labor Union of Arakan and Ko Hla Thein Tun, a

member of the Arakan League for

Democracy.

Reported by the Assistance Association for Political

Prisoners (AAPP) in an interview on July 12, 2002.44

Even those who have been recognized as 'Persons of Concern' by the UNHCR are

often not safe.

My

friend, Saw Htoo Aung [a political activist] had just received UNHCR refugee status

in Bangkok before he was arrested on October 27, 2002. When he showed his UNHCR

certificate, the people would not recognize it. He called me from the police

station asking me to help pay money to the police. I had no money to pay for

him. I tried to look for money and also to inform UNHCR's Burmese section. The

officials for that section told me not to worry. Before I could do anything, he

was deported to Mae Sot on October 29, 2002. He was sent directly to the

Burmese authorities where he was immediately arrested and had no way to escape

back to Thailand. The Thai immigration officers were just watching. He was

arrested with his biography and the UNHCR letter and photos of his friends.

A former Burmese student interviewed in Bangkok on

October 30, 2002.

Those who are not deported still live in a state of constant fear and anxiety

and are subjected to harassment and exploitation.

Late June 2002, five Burmese 'political student

activists' were having dinner at a small restaurant in Chiangmai, Thailand. At the same time and

place, about five off-duty police men were also having dinner. The police

overheard the conversation and realized they were political refugees from

Burma. The police called an additional five off-duty police officers (all in

their off-duty uniforms) and attacked the Burmese as they left the restaurant.

The Burmese called other Thai intelligence contacts. Upon arrival the students

were taken aside and the intelligence officer negotiated for the return of

their belongings (which were taken earlier). The students realized that 9,000

baht (US$250) was missing from their belongings. However, they were told not to

pursue the problem as there really is nothing that can be done without risk of

their arrest and deportation. Those from

Burma agreed not to try and recover the stolen money, realizing their situation

and the severe consequences.

Two Bamar males involved in the incident who were

interviewed on September 4, 2002 in Chiangmai.

Police in Kanchanaburi's Sangkhlaburi district arrested

31 Burmese nationals on Tuesday [August 20, 2002], claiming they were illegal

workers and pushed them back over the border. Forum Asia, the human rights

group, identified at least 14 of the Burmese as members of dissident groups....

At least three activists were carrying ID

cards issued by the UNHCR.... Thailand has always been a land of refuge for people of all creeds fleeing peril.

Now, under the guise of a crackdown on illegal labor, the government will undo

decades of good will....45

In addition to the many Thai citizens who are concerned

about such actions, Aung San Suu Kyi has spoken out on the issue of treating

political dissidents and pro-democracy activities as illegal migrants.

It is not appropriate to crackdown on dissidents and

pro-democracy activists who do not break the laws [in

their host countries].46

Taxation and Loss of

Livelihood

People

who have left Burma cite instances of heavy taxes levied in what appear to be arbitrary

and unexplained ways. These 'taxes' are not only monetary in nature, but often

take the form of a percentage of one's harvest or livestock.

It was really hard to earn a living. I am only a woman

and had to look after three children too. I couldn't really work on the farm. I

worked if anyone employed me. If there was no job, I couldn't eat anything. I

really suffered. Sometimes the Burmese military asked for something and I had

to find it for them. If the government

forced me to do duties, I couldn't refuse. If I couldn't go, I had to hire someone

else in the amount of 300 kyat to go in my place. I could not afford to

hire someone else, because I

didn't even have any money. If we gave rice to the government for our taxes instead of 10,000 kyat, we had to give 300 or

400 basins per year. I didn't have this either. I couldn't bear it. I arrived

in Thailand ten days ago with my children. Now I have a debt of 5,000

baht to pay the transportation fees for all

of us.

A 30-year-old Shan female interviewed on March 26, 2002,

just after her arrival along the Thai border in Chiangmai Province.

I

moved to Thailand because I can work and make money. When living in Shan State, we just barely survived and couldn't save

any money. Sometimes we had to give a half basin of rice to the Burmese

military each time they asked. We couldn't

refuse. If we didn't give it, they would come and find fault with the headman.

Then he would ask us to give the rice. If we didn't have it, we had to sell some of our property to buy rice to give.

A 27-year-old Shan female interviewed on March 23, 2002,

three days after arriving on the Thai border in Chiangmai Province.

When I stayed in Burma,

I worked on both a rice and a poppy farm. I worked on the rice farm part of the

year, then after harvesting the rice, I worked on the poppy farm. The Burmese

military came and forced us, the villagers, to grow poppy crops. We were not able to refuse them. After harvesting it, they

forced us to sell it to them. We divided the harvest into three parts.

The military took two parts and gave us only one part. Our earnings were not

sufficient to live on. A 30-year-old Shan male interviewed on March 26, 2002, one

day after arriving along the Thai border in Chiangmai Province.

...There

is a daily opium fee of 10 'kyat-thar' [approximately 150 grams]. If you don't

grow opium you have to pay in cash. We had to sell off our rice to get the

cash. I don't know why, but they demanded it.

An ethnic Lahu man interviewed in June 2000, working on

a farm along the Thai border.

A family's crops and animals might also be destroyed by

the Burmese military as a form of harassment and intimidation, leaving no way for families

to survive.

... I

am a farmer, but there is danger in my home village. The army columns destroyed our rice paddy, let their donkeys eat

our harvest, and destroyed the leftover rice. When a column arrives we

flee to the forest and when they leave we return...but now there are landmines

in our rice fields. I have six children, including twin infants, four months

old. Their mother's milk was not enough, so we decided to go...

A 39-year-old Karen man interviewed in May 2000, in Mae

La camp along the Thai border.

Economic Conditions

The economic struggles in Burma are

severe and documented in detail in the 1999 World Bank report: Myanmar: An Economic and Social

Assessment. As the report details, the economic

climate and policies of the Burmese government suggest dire consequences for the people:

... If

present policies are maintained, the people of Myanmar are unlikely to benefit

substantially from a resumption of growth in the region, the domestic

agricultural and private sectors will be unable to fulfill their potential, and

the pressure on living standards will continue. Continuing lackluster economic

performance that fails to improve living standards for the majority of the population could have devastating consequences

for poverty, human development and social cohesion in Myanmar.

Given this forecast and the sense of hopelessness that

fundamental political and economic changes will not come soon to Burma, people see

no other option but to go abroad.

We

have been forced to leave our village twice because of the war. It is not because I just wanted to stay here peacefully

that I came. How can I just leave my parents behind? So, I will go back,

but I don't know yet when to go. If I can work and make some money, I will go back. The Thai government doesn't need

to push me back. But right now the little money I borrowed to come here

is used up, so I will have to make money

first.

A 29-year-old Shan female interviewed on April 12, 2002,

ten days after arriving in Chiangmai Province, Thailand.

Farming was our livelihood in Burma. My parents owned

seven acres of land and we cultivated rainy season paddy regularly. By the order of

the government, the past four years we have also had to cultivate dry season

paddy during the summer. We always go in debt with the dry season paddy. Last

year, our rainy season crop failed also and we got only 40 percent of our usual

harvest, but we still had to give the

government the same quota as every year. To fulfill our quota we had to

mortgage our fields for a loan at the interest rate of 15% to purchase the

paddy needed to meet our quota. This year the government has ordered that dry season paddy must be planted and those who

fail to do so will have their land confiscated. We have so much debt, I had to come to Thailand. A 25-year-old Tavoyan

woman interviewed on February 13, 2002, just after she arrived along the Southern Thai border.48

People

come to Thailand because of the economy in Burma. No one can survive with the

terrible economic problems and high prices for basic commodities. People's income and spending can never be

balanced. One must earn at least 6,000 to 15,000 kyat a day to feed a

family. But, a laborer earns only about 200 kyat

each day. You cannot eat for a day on this. In addition, we have to pay taxes whether

we worked the land or had a good harvest. We had to pay or they would put

us in jail. So we often have to borrow money from others and then become heavily in debt. Because of these debts, many

people leave Burma

to find work in other

countries. I would say about 75 percent of young people, 18 to 40 years of age,

go abroad. You rarely see young people in the streets of Burma now .It doesn't mean that I really wanted to come [to Thailand],

it was just too hard to earn a living. It is not because I just want happiness and

wealth. If I could work and make some money, I would go back immediately,

because my parents and relatives are still

all there.

A 42-year-old Bamar male interviewed in Tak Province one week after his arrival in January 2002.

In

Burma, no one's income is enough and people always need to borrow money from

somewhere. Ordinary workers' income is about 400 or 500 kyat (25 baht) a day. I

worked as a conductor part time while I was studying in grade 10. My father and

mother worked full time. Our household's daily expenses would be 1,000 kyat a

day or sometimes even more. But, if you have a tenth grade student in your

house, that would cost at least 20,000 kyat a month. My parents must spend that

much money for me only. Therefore, I had to quit school. I decided to come to

Thailand to get a job. All my friends already went abroad. I think if the

government can control the prices of commodities, and if they reduce or cut all

the taxes people will not go to other

countries. For now, we have to pay so many different kinds of tax and

everything becomes so expensive.

A

23-year-old Bamar who arrived in Thailand in

January 2002, and was interviewed the following month along the border in Tak Province.

IV. FEAR OF RETURN

The violence and abuses encountered in Burma not only

fuel the exodus, but also result in migrants' willingness to tolerate extensive

human rights abuses in Thailand, fearing their deportation back home as even more threatening.

Those interviewed repeatedly voiced their

reticence about returning:

I don't have any plans. I don't want to go back. If we go

back, we will surely suffer.

A 30-year-old Shan female interviewed on March 26, 2002,

after just arriving along the Thai border in Chiangmai Province.

Everything will be the same if I go back.

So who wants to go back? When I work here if I earn one baht, it will be mine

instantly. But in Burma, if they don't leave us alone, we cannot eat

at all. If we work three parts, we have to give them two, leaving only one for

our survival. Here, there is no forced labor. If the owner forced us to work, he pays us too. In our

country, we worked very hard, but it still was not enough. So think

about this! We had to pay 100-200 kyats for the tax per acre. If we sold to other people, the price was 750 kyat for two kilos

of paddy. If we didn't pay the tax, they forced us to sell to them the price of

250 kyats for two kilos of paddy ... What could we do, but cool down and give

them what they want.

A 29-year-old Shan female interviewed on April 22, 2002,

after arriving along the Thai border of Chiangmai Province ten days earlier.

I am

afraid to be sent back. Even if the Thai authorities put me on an airplane to

go back, I will find a way to return here again. I don't want to talk about

going back any more. For me going back is like going to meet tigers and lions

only. I never think about wanting to be

well-off. If I stayed in our country and could work independently,

moreover, without being tortured, I would not want to leave my hometown at all.

An unemployed 40-year-old Shan male interviewed on April

21, 2002, the day after arriving at the Thai border in Chiangmai Province.

In addition to the fears migrants experienced as the

victims of human rights violations in Burma before they fled, they also

harbor fears of arrest, detention and/or hefty fines should they return.

According to Burma's Immigration Act of 1947:

No citizen of the Union of Myanmar shall enter the Union

of Myanmar without a valid Union of Myanmar Passport or a certificate in lieu

thereof, issued by a competent authority

(Act 3.2).49

The billboard hanging at the Kawthong Immigration Gate

reminds those leaving or returning

to Burma of this law and its penalty.

SPDC's

Law 367/120 -(b) (1) Burmese citizens who illegally

want to go and work in Thailand

will be sentenced to a seven-year prison term.50

To implement this policy the Immigration Department of

Myanmar chose 22 divisions and formed a team for the Prevention of

Illegal Immigrants.51 However, the laws have been

applied arbitrarily and there are constant reports of extortion and lack of any

legal proceedings

in their implementation. For example:

On

October 5, 2001, the Tenasserim Division's General Administration Department

notified all police stations, immigration departments and township-level authorities of the new law whereby

'sentencing is divided into three sections

depending on one's age and

residence.... If the fines can be paid the subjects will reportedly be returned to their homes and have

their movements restricted. '52

Since the

mid-nineties the regional command of Eastern Shan State implemented measures to restrict women under the age of 25

traveling into Thailand with the aim of controlling trafficking.53

As one young man

recounted:

Recently, all the Burmese government checkpoints stop

young people, especially women and girls from going to border towns. They also

dragged me out from the bus at a checkpoint along with many other young girls.

We had to pay 1,000 kyat each. Then, they allowed us to continue on the same

bus.

A 17-year-old Bamar male interviewed in January 2002,

after arriving along the Thai border in Tak Province earlier the same month.

The fear of returning home to Burma

is most visible when witnessing the extent of abuses and hardships

undocumented migrants from Burma endure

in order to stay in Thailand. The ongoing violations

encountered by migrants from Burma, come from many quarters including other

migrants, employers, government officials (on both sides of the border), local community members and other stakeholders.54

I left home one month ago. When we got here we met Thai

soldiers at the checkpoint. I lost over 20,000 baht to them. They met us when

we came here then they asked to check our clothes and bodies. But I left my

money with my elder sister, because she had

a Thai ID card. So, I thought there was no problem. When they searched

my body, they didn't get or see anything. Then they called me to their hut and

said that if I didn't give them any money, they would put me in jail. They

ignored whatever I said. Any way they had to get some money from us because

they saw the money with my sister. I had sold all my properties at my house to

get some money. When I met this problem I didn't have anything left. I feel depressed

and down-hearted now.

A 35-year-old Shan female interviewed on March 25,

2002, after arriving on the Thai border in

Chiangmai Province.

I am afraid. If we stay here, we don't have any ID card. If we go back, it is difficult

to earn a living there and not starve. So, who wants to go back? We already know what happens there. But here, even

if the police catch us, they just ask for money. I think they won't beat

us up or kill us like in Burma.

A 30-year-old Shan male interviewed on March 26, 2002,

after arriving the day before along the Thai border in Chiangmai Province.

Undocumented migrants seek work not